WASHINGTON — The Trump administration, racing a surging Covid-19 death toll, instructed states on Tuesday to immediately begin vaccinating every American 65 and older, as well as tens of millions of adults with medical conditions that put them at higher risk of dying from coronavirus infection.

The federal government will release all available doses of the vaccine instead of holding about half in reserve for second doses, Alex M. Azar II, the health secretary, said, adding that states should start allowing pharmacies and community health centers, which serve largely poor populations, to administer the shots.

The announcement came as Covid-19 deaths have soared to their highest levels in the pandemic, and the incoming administration of Joseph R. Biden Jr. has promised a far more aggressive, federally driven vaccination effort.

And it came with a cudgel: States will lose their allocations, Mr. Azar said, if they do not use up doses quickly. And starting in two weeks, state vaccine allocations will be based on the size of a state’s population of people 65 and older, not on the general population. It was unclear, however, whether that would hold past Jan. 20, when Mr. Biden takes office.

“This next phase reflects the urgency of the situation we face,” Mr. Azar said. “Every vaccine dose that is sitting in a warehouse rather than going into an arm could mean one more life loss or one more hospital bed occupied.”

The major policy shift was driven by vaccinations getting off to a slow start, though the pace has picked up considerably over the past week. It comes as some states have already begun vaccinating people 65 and older, leading to long lines and confusion over how to get a shot.

The new policy could exacerbate that confusion in states that have been following their own carefully laid timelines for getting the vaccine to various priority groups — including teachers, emergency responders, grocery store employees and other types of essential workers, whom Mr. Azar did not mention at all in his announcement.

Only a handful of states have already opened vaccination to everyone 65 and older, including Florida, Alaska, Michigan and Texas. And only Texas has also offered shots to all of its residents with at least one chronic medical condition.

Other states had planned to widen access to older residents gradually. Ohio, for example, was to start vaccinating people 80 and older next week, people 70 and older on Feb. 1 and those 65 and older on Feb. 8. Florida has been overwhelmed with demand from its 65-plus population, with new online registration portals quickly crashing and people spending hours on the phone or in long lines, often in vain.

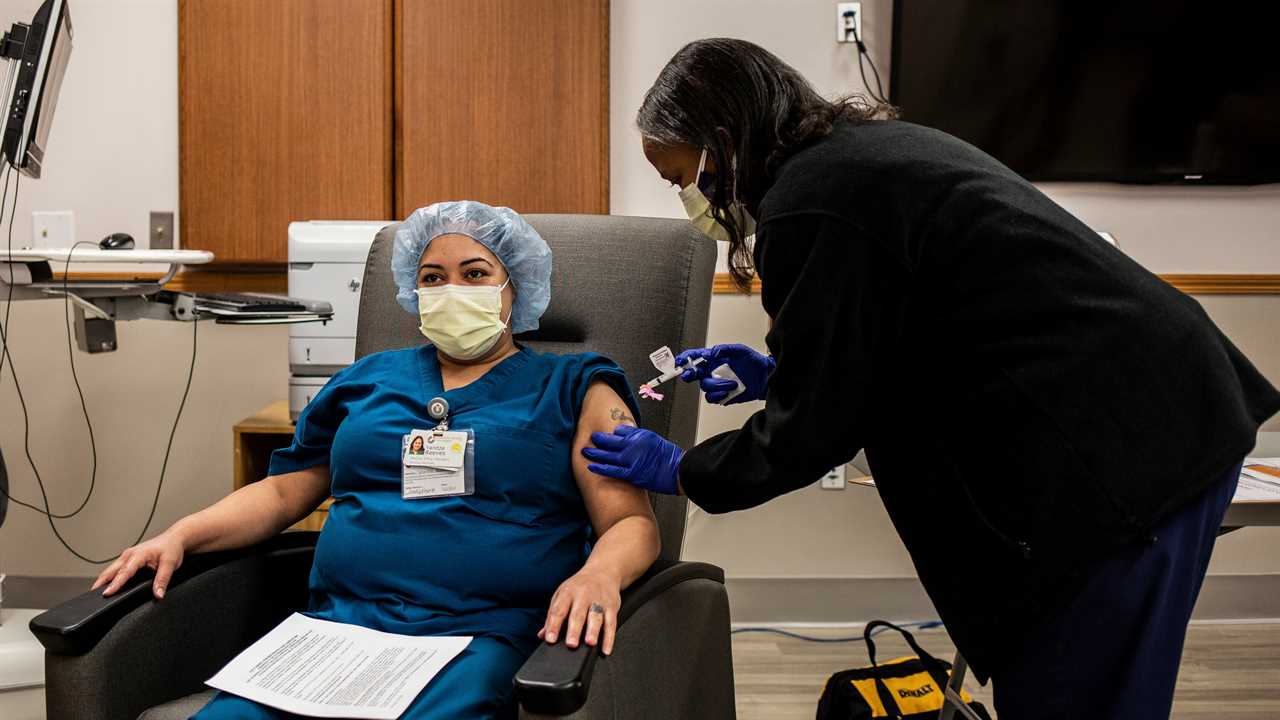

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended last month that after vaccinating health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities, states should vaccinate people older than 75 and certain “frontline” workers who cannot do their jobs from home. Only after that, the C.D.C. advised, should states turn to people ages 65 to 74 and adults of all ages with high-risk medical conditions. The C.D.C. recommendations were not binding, but many states have largely been following them while demand still far exceeds supply.

How Mr. Azar’s enforcement threat will work is unclear; in two weeks, Mr. Biden will already have been sworn in as president. Mr. Azar said the incoming Biden administration would be briefed on the changes, though he added that Americans “operate with one government at a time, and this is the approach that we believe best fulfills the mission.”

Mr. Biden is expected to announce details of his own vaccination plan — which will include federally supported mass vaccination clinics — this week. The Biden transition team declined to comment on Tuesday on the new Trump policy. But a person familiar with the president-elect’s plans said Mr. Biden had also been planning to expand the universe of those who are eligible to be vaccinated.

Mr. Azar said people seeking shots because they have high-risk medical conditions would need to provide “some form of medical documentation, as defined by governors,” but he did not elaborate. A significant portion of the population has conditions that the C.D.C. has determined increase the risk of severe Covid disease, starting with obesity, which affects at least 40 percent of adults.

Other individuals who would qualify for vaccines immediately under Mr. Azar’s directive include the more than 30 million adults with heart conditions, 37 million who have chronic kidney disease and 1 in 10 who have diabetes.

The new distribution plan, first reported Tuesday morning by Axios, is a reversal for the Trump administration, which had been holding back roughly half of its vaccine supply — millions of vials — to guarantee that second doses would be available. Mr. Azar said the administration always expected to make the shift when it was confident in the supply chain.

Dr. Paul Offit, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and a member of the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory panel, praised the administration’s decision, likening the current situation to the Titanic, where there were not enough lifeboats to save everyone, “and you have to decide who you are going to let on.”

“Without question there will be people who will die over the next three or four months because they didn’t get this vaccine,” Dr. Offit said. “It’s tragic.”

Dr. Grace Lee, a pediatrician at Stanford University and member of the expert committee that came up with the C.D.C.’s recommendations for prioritizing the vaccine, said she was eager to see far more people get vaccinated but concerned that some particularly vulnerable groups could get lost in the shuffle.

“We should make sure we keep to outcomes in mind at the national level: efficiency and equity,” Dr. Lee said. “We see a lot of discussions and challenges on efficiency, but we cannot lose sight of the equal importance of equity as an important distribution principle.”

Just days ago, Mr. Azar and officials from Operation Warp Speed, the administration’s fast-track vaccine initiative, criticized aides to Mr. Biden for announcing a similar plan to increase the number of doses landing in states. Mr. Azar said at the time that releasing nearly all of the doses, as the Biden team proposed, would jeopardize the “system that manages the flow, to maximize the number of first doses, but knowing there will be a second dose available.”

Nearly 380,000 people have died from Covid-19 in the United States since the start of the pandemic. In recent days, the number of daily deaths in the country has topped 4,000.

As of Monday, about nine million people have received at least one dose of a Covid-19 vaccine, the C.D.C. said, far short of what the federal government initially promised. At least 151,000 people in the United States had been fully vaccinated as of Jan. 8, according to a New York Times survey of all 50 states. But Mr. Azar said Wednesday that the country was “on track” to reach the rate of one million vaccinations a day in a week or so. He said the perceived delay in using up doses is at least partly because of slow data collection.

The idea of using existing vaccine supplies for first doses has raised objections from some health workers and researchers, who worry that front-loading shots will raise the risk of second injections being delayed. Clinical studies testing the vaccines showed the shots were effective when administered in two-dose regimens on a strict schedule. And while some protection appears to kick in after the first shot, experts remain unsure of the extent of that protection, or how long it might last without the second dose to bolster its effects.

But others have vocally advocated explicit dose delays, arguing that more widely distributing the partial protection afforded by a single shot will save more lives in the meantime.

Even before Tuesday’s order, health experts and state officials have faced difficult choices as they decided which groups would be prioritized in the vaccine rollout. While older Americans have died of the virus at the highest rates, essential workers have borne the greatest risk of infection, and the category includes many poor people and people of color, who have suffered disproportionately high rates of infection and death.

Despite his state’s bumpy rollout, Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida, who prioritized people 65 and older from the start, said he believed making all older people eligible was always the right thing to do.

The initial guidelines “would have allowed a 20-year-old healthy worker to get a vaccine before a 74-year-old grandmother,” Mr. DeSantis said on Tuesday at a news conference in the sprawling retirement community called The Villages. “That does not recognize how this virus has affected elderly people.”

In New York, which began vaccinating people 75 and older and more essential workers this week, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo said that the state would accept the new federal guidance to prioritize those 65 and older, though he criticized the administration for not clearly defining who should be considered “immunocompromised.”

The new guidance will make more than seven million New Yorkers eligible for the vaccine, Mr. Cuomo said, though the state currently receives only 300,000 doses a week.

“The federal government didn’t give us an additional allocation,” he said. “At 300,000 per week, how do you effectively serve seven million people, all of whom are now eligible, without any priority?”

New Yorkers 65 and older are immediately able to schedule appointments on the state’s website, according to Melissa DeRosa, a top Cuomo aide, who added that the state was working with the C.D.C. on who is considered to have compromised immune systems.

New guidelines released on Monday by the C.D.C. now note that while people should get their second shots “as close to the recommended three-week or one-month interval as possible,” there is “no maximum interval between the first and second doses for either vaccine.”

The update perplexed experts, who said that while other, previously licensed vaccines that involve multiple doses could be administered months or even years apart, no evidence yet exists to clearly support this strategy for Covid-19. “They will need to back this up with data,” said Marion Pepper, an immunologist at the University of Washington.

Health officials in Britain are now allowing intervals between the first and second doses of Pfizer’s vaccines of up to 12 weeks. Last week, the World Health Organization said the injections could be given up to six weeks apart.

In response to queries about dose delays, representatives from Pfizer and Moderna have repeatedly pointed to the company’s clinical trials, which tested dosing regimens of two shots, separated by 21 days for Pfizer and 28 days for Moderna.

“Two doses of the vaccine are required to provide the maximum protection against the disease, a vaccine efficacy of 95 percent,” Steven Danehy, a spokesman for Pfizer, said this month. “There are no data to demonstrate that protection after the first dose is sustained after 21 days.”

Representatives from the C.D.C. did not respond immediately to requests for comment.

Katie Thomas contributed reporting from Chicago, and Roni Caryn Rabin from New York.