The Food and Drug Administration on Friday authorized the coronavirus vaccine made by Moderna for emergency use, allowing the shipment of millions more doses across the nation and intensifying the debate over who will be next in line to get inoculated.

The move will make Moderna’s vaccine the second to reach the American public, after the one by Pfizer and BioNTech, which was authorized just one week ago.

The F.D.A.’s decision sets the stage for a weekend spectacle of trucks rolling out as expert committees begin a new round of discussions weighing whether the next wave of vaccinations should go to essential workers, or to people 65 and older, and people with conditions that increase their risk of becoming severely ill from Covid-19.

Jockeying for the next shots in January and February has already begun, even though there is still not enough of the two vaccines for all the health care workers and nursing home staff members and residents given first priority. Uber drivers, restaurant employees, morticians and barbers are among those lobbying states to include them in the next round along with those in the more traditional categories of the nation’s 80 million essential workers, like teachers and bus drivers.

The rapid progress from lab to human trials to public inoculation has been almost revolutionary, spurred by the nation’s urgent need to blunt the pandemic that has broken record after record in U.S. deaths, hospitalizations and economic losses. In the last week alone, there has been an average of 213,165 cases per day, an increase of 18 percent from the average two weeks earlier. And the daily death toll in recent days has surpassed 3,200.

Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, called the advent of two vaccines “an historic moment.”

“This to me is a triumph of multiyear investment in biomedical research that culminated in something that was not only done in record time, in the sense of never before has anybody even imagined you would get vaccines to people in less than a year from the time that the sequence was made known,” Dr. Fauci said.

“This is an example of government working. It worked really well,” he added.

Moderna, a company based in Cambridge, Mass., worked with Dr. Fauci’s agency at the National Institutes of Health to create a vaccine that, along with Pfizer-BioNTech’s, shepherds in a new technology based on genetic material called messenger or mRNA. In clinical trials in tens of thousands of volunteers, the vaccines proved 94 to 95 percent effective. Each requires two shots.

Both products are reaching an anxious public before vaccines made with traditional approaches, and have become even more critical as other companies’ efforts have faltered in recent months.

The emergency authorization kicks off a swift and complex drive to distribute some 5.9 million doses of the Moderna vaccine around the country, with shipping to begin on Sunday and deliveries starting on Monday. The first Moderna vaccinations could then be given hours later.

Because Moderna’s vaccine, unlike Pfizer-BioNTech’s, does not need extreme-cold storage and is delivered in smaller batches, states are hoping to provide it to less populated areas, reaching rural hospitals, local health departments and community health centers that were not at the top of the distribution list.

Three places that did not receive the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine — the Marshall Islands, Micronesia and Palau — will receive the Moderna vaccine for that reason, according to a federal health official familiar with the government’s distribution plans.

And in contrast to Pfizer’s rollout last week, the Moderna vaccine deliveries will be managed by the federal government under the funding of Operation Warp Speed, the administration’s program to develop and distribute vaccines as fast as possible.

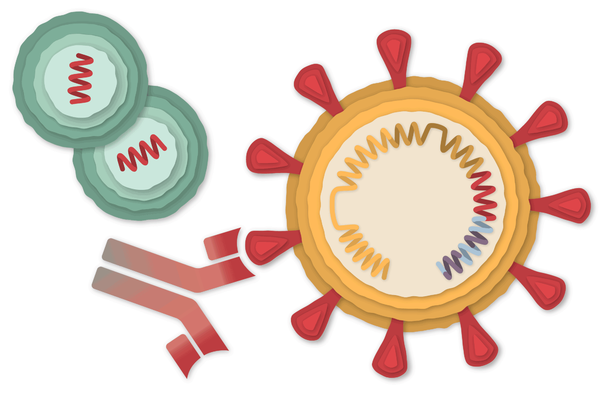

How Moderna’s Vaccine Works

Two shots can prime the immune system to fight the coronavirus.

Supplies of a second vaccine cannot come soon enough. Several governors and state health officials said on Friday that they were dismayed to learn they would be getting less of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine next week than the federal government had promised.

Dr. Mark Levine, commissioner of the Vermont Department of Health, said in a Friday briefing: “All my colleagues in the region are reporting a 25 to 35 percent decrease in their allocation for next week. As we were walking in, I learned as many as 975 doses out of an expected 5,850 doses would not be coming in when we expected. That doesn’t mean we won’t be getting all of those doses. It just means they won’t be coming in when we expected.”

He added, “What everyone around the country is upset about, in addition to just the number, is there’s been no communication, so there’s no understanding of what this really means.”