WASHINGTON — The far-reaching economic package Democrats are assembling as a companion to whatever emerges from bipartisan infrastructure talks is itself a precarious proposition, facing steep obstacles because of its sheer size and scope in a party whose congressional majorities have little room for dissent.

The contours, which Senate Democrats have just started to sketch out, reflect a deep desire to deliver on ambitious campaign promises, accomplish major policy goals long frustrated by Republican opposition and avoid what many of them see as the pitfalls of 2009, when Democrats in power narrowed their domestic ambitions to win conservative votes that never fully materialized.

But the package, which Democrats said this week could cost up to $6 trillion, faces major challenges, including resistance among moderates wary of so much federal spending. Senate rules also strictly limit what Democrats can accomplish if they want to steer clear of a filibuster using the fast-track budget reconciliation process, which would be its only path through a Senate divided 50 to 50.

The process promises to be far more challenging than the one that led to the enactment, just two months into President Biden’s tenure, of his nearly $1.9 trillion pandemic relief bill, which passed over Republican opposition with the support of all but one Democrat.

In this case, liberal Democrats are placing many of their domestic policy hopes into what is shaping up as a single, extraordinarily ambitious package that many regard as their only remaining chance to accomplish key priorities this year.

They have watched with alarm as a group of Republicans and Democrats hashes out a potential compromise that covers only traditional physical infrastructure and omits many of their marquee goals, and are determined to use their majorities to fashion a plan more reflective of their desires.

It began taking shape this week, as Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the majority leader, convened Democrats on the Budget Committee to discuss potential measures including climate change provisions, caregiving subsidies, paid leave, tax increases on wealthy individuals and corporations, Medicare expansion and legal status for millions of undocumented immigrants.

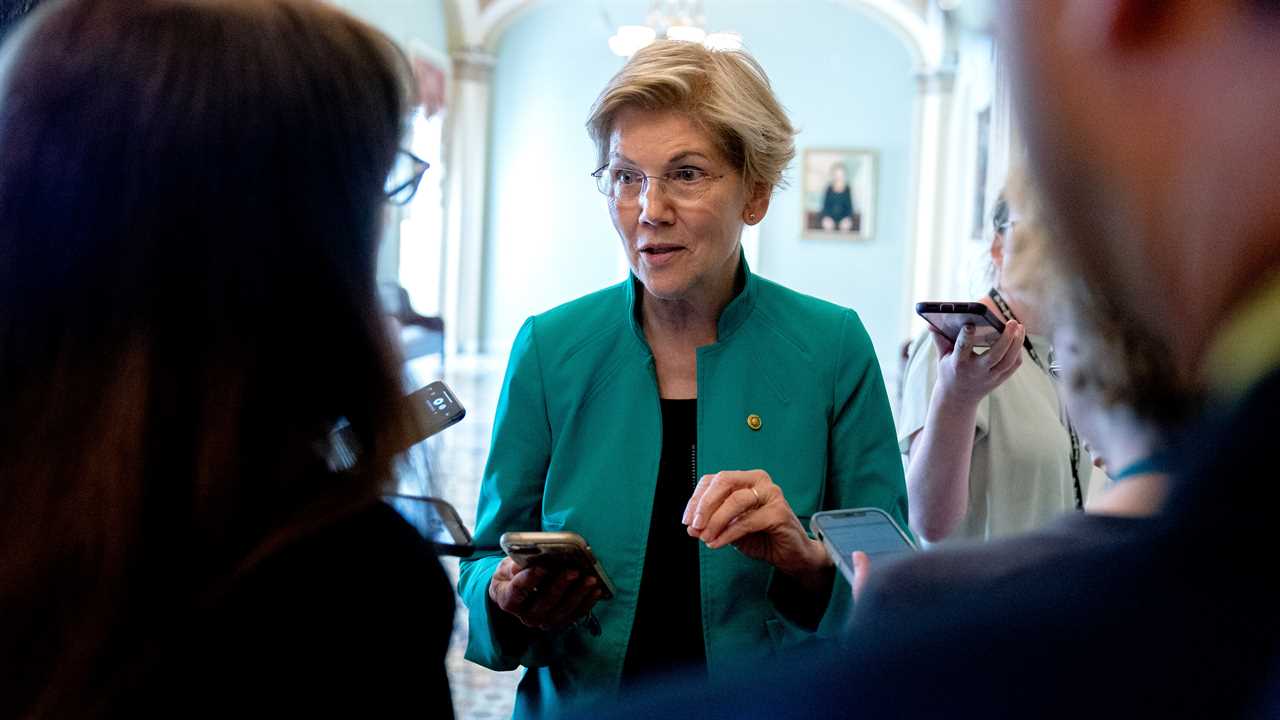

“It’s not so much about debating one number,” said Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a Democrat who has pushed for a sweeping package. “It’s about what does it take to get the work done — and $6 trillion sounds about right.”

Senator Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent who is chairman of the Budget Committee, “started with the question of what needs to be covered and how much does it cost realistically to get there,” she added.

But lawmakers and aides acknowledge that it is unlikely that Democrats will have the votes for all those ambitions, given that nearly all House Democrats and all 50 senators who caucus with Democrats would have to support it to overcome Republican opposition. On Monday, five House Democrats wrote to Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California warning about the fiscal consequences of a huge spending measure, calling for Congress to pass a budget blueprint that “stabilizes the debt as a share of the economy” before taking up spending or tax legislation.

Politics Updates

- The U.S. is working to fulfill a pledge to send some doses abroad by replacing AstraZeneca vaccine with others.

- Bipartisan legislation aims to help Afghans who aided the U.S. military get visas.

- Trump endorses Kelly Tshibaka, Murkowski’s challenger in Alaska’s Senate race.

“As we continue to have a national conversation about major infrastructure spending and necessary investments to support hardworking American families, we believe it is critical that we do so responsibly and take meaningful steps to get our fiscal house in order,” the lawmakers wrote. The group included Representatives Carolyn Bourdeaux of Georgia, Stephanie Murphy of Florida and Kurt Schrader of Oregon.

Any reconciliation measure would be subject to strict rules that would most likely force changes or the outright elimination of certain provisions if they are deemed unrelated to federal revenue. Aides and advocacy groups are working to ensure that such measures, particularly those addressing climate change, can remain in the bill.

The Biden administration has called for a national network of charging stations for electric vehicles and consumer rebates to pivot consumers away from combustion engines; tax incentives to drive solar, wind and other clean energy development; and a standard that would require power companies to increase the amount of clean electricity they generate over time until they eventually stop burning fossil fuels.

But the politics could prove tricky: Senator Joe Manchin III, Democrat of West Virginia, where coal dominates the economy, has expressed skepticism about a clean electricity mandate. A crucial player in the talks on a bipartisan infrastructure package, Mr. Manchin has also declined to publicly commit to supporting the reconciliation package as he works with other Democrats and Republicans to hammer out the details of a far more limited compromise plan totaling $1.2 trillion over eight years, with $579 billion of that in new spending.

Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, another key centrist Democrat, has also declined to say whether she would support a separate reconciliation measure, even as liberals warn that they will not accept the compromise bill without receiving assurances that a reconciliation package would then have the support needed to also pass. A spokesman said Ms. Sinema would consider any idea to strengthen Arizona’s economy, without explicitly addressing the process.

That has led to a complex and freighted dynamic for Democrats on Capitol Hill, in which the discussions around what should be in the reconciliation package hinge in part on the outcome of the bipartisan infrastructure negotiations, and vice versa.

For now, it is unclear whether the White House and enough congressional Democrats will sign off on the emerging bipartisan proposal to ensure its passage.

The White House issued a statement on Friday reiterating that Mr. Biden would not support raising the gas tax, after the bipartisan group spent days weighing whether to include a provision indexing the gas tax to inflation.

“The president has been clear throughout these negotiations: He is adamantly opposed to raising taxes on people making less than $400,000 a year,” said Andrew Bates, a White House spokesman. “After the extraordinarily hard times that ordinary Americans endured in 2020 — job losses, shrinking incomes, squeezed budgets — he is simply not going to allow Congress to raise taxes on those who suffered the most.”

As an alternative, White House officials are discussing raising more revenue by giving the I.R.S. more resources than previously discussed by the bipartisan group to crack down on wealthy corporations and individuals that are not paying the taxes they owe.

It is unclear how and when the centrist group will ultimately agree to finance its plan.

As for the reconciliation package, Democrats have said they plan to include as much as $2.5 trillion in tax increases. But first they would have to find the votes to do so.

Lisa Friedman contributed reporting.