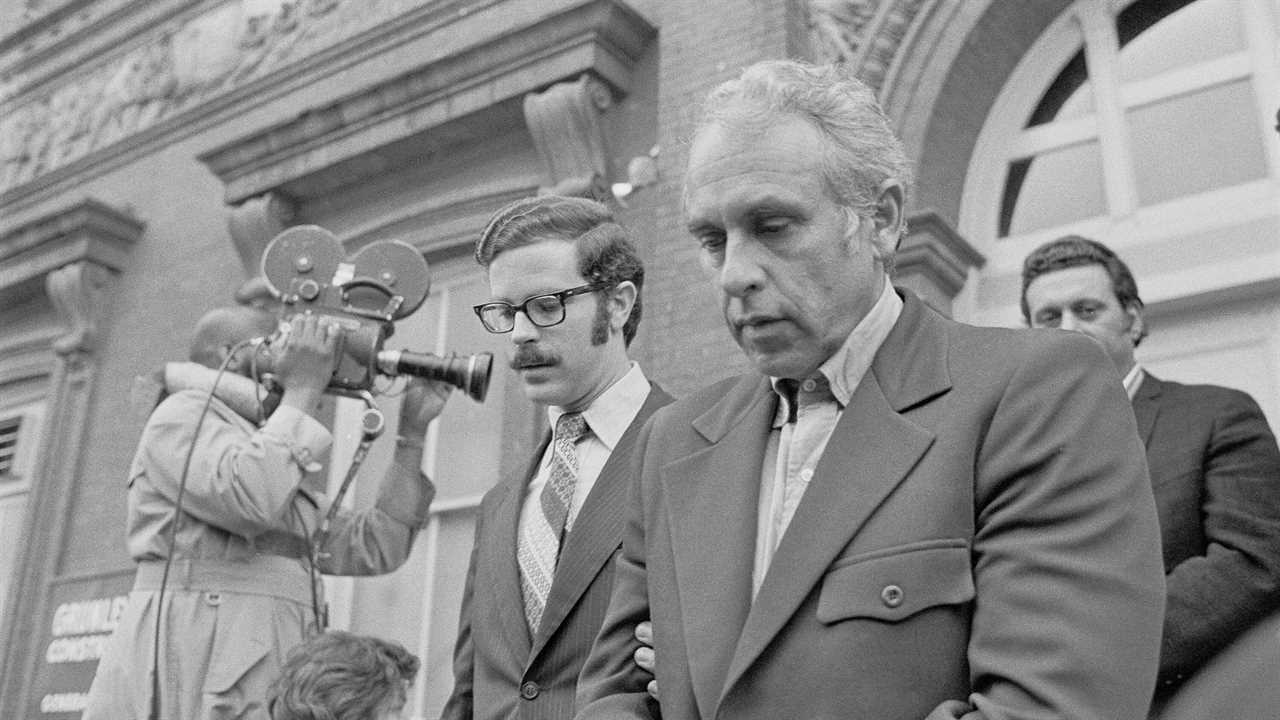

Eugenio Martinez, the last surviving Watergate burglar and the only figure in the scandal besides Richard M. Nixon to be granted a presidential pardon, died on Saturday in Minneola, Fla. He was 98.

His death, at his daughter’s home near Orlando, was announced by Brigade 2506, a veterans group of Mr. Martinez’s fellow anti-Communist Cuban exiles. Their abortive invasion to overthrow the government headed by Fidel Castro in 1963 at the Bay of Pigs was covertly supported by the Central Intelligence Agency.

Mr. Martinez was indelibly linked to a crime that set in motion the downfall of a president. “I wanted to topple Castro, and unfortunately I toppled the president who was helping us, Richard Nixon,” Mr. Martinez said in an interview with the Spanish newspaper El Mundo in 2009.

Mr. Martinez, who was said to have infiltrated Cuba hundreds of times on missions to plant anti-Castro agents there or extract vulnerable Cubans, was one of four operatives recruited in 1972 to burglarize the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate complex in Washington. He said he had been enlisted by E. Howard Hunt, another Bay of Pigs veteran and C.I.A. alumnus.

By Mr. Martinez’s account, the burglars were instructed to search for proof that Castro was subsidizing the campaign of Nixon’s Democratic rival for re-election, Senator George S. McGovern.

On June 17, 1972, on their second foray into the Watergate offices — to fix problematic listening devices that they had planted weeks earlier, the authorities said — they caught the attention of an alert security guard, who notified the police.

In January 1973 four of the five burglars — members of the so-called plumbers, an informal White House team assigned to plug information leaks — pleaded guilty so as to avoid revealing details of the bungled operation. They were convicted of conspiracy, theft and wiretapping.

The others, all Cuban-born, were Bernard L. Barker, a former Miami real estate agent and C.I.A. operative, who died in 2009; Virgilio González, a Miami locksmith, who died in 2014; and Frank A. Sturgis, a soldier of fortune, who died in 1993. (In 1971, the four had also taken part in the break-in at the Los Angeles office of the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg, the former Defense Department analyst who disclosed the Pentagon papers to the press.)

Each of the four served about 15 months in prison. Mr. Hunt served about 31 months.

They were led by James W. McCord Jr., a security coordinator for the Nixon campaign whose confession to the judge just before his sentencing precipitated the revelations of White House crimes and cover-ups that culminated in Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

In 1977, the four Cuban-born burglars each accepted an out-of-court settlement of $50,000 from the Nixon campaign. They said that they had that been misled into believing that they were acting with government sanction on behalf of a White House administration that was concerned about American security and sympathetic to Cuban refugees.

In 1983, after his requests for a clemency had been rejected by Presidents Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter, Mr. Martinez — who, it turned out, had still been on retainer to the C.I.A. at the time of the Watergate break-in — was pardoned by President Ronald Reagan.

The pardon, which was granted because Mr. Martinez had been regarded as the least culpable of the defendants, restored his right to vote. Despite the ordeal, he prided himself on one Watergate keepsake — a golden lucky clover inscribed, in Spanish, with the words “Good luck, Richard Nixon.”

Eugenio Rolando Martinez Careaga was born on July 7, 1922, in what is now the province of Artemisa in western Cuba. Before Castro’s rise he was exiled as a critic of the dictator Fulgencio Batista. He later returned to Cuba but left again in 1959 for opposing Castro’s newly installed regime.

“My mother and father were not allowed to leave Cuba,” he wrote in a reminiscence published in Vanity Fair in 1974. “It would have been easy for me to get them out. That was my specialty. But my bosses in the Company — the C.I.A. — said I might get caught and tortured, and if I talked I might jeopardize other operations. So my mother and father died in Cuba. That is how orders go. I follow the orders.”

He is survived by his daughter, Yolanda Toscano, and two grandchildren.

After leaving prison, Mr. Martinez worked in real estate and as a car salesman. He became known as Musculito (or Little Muscle) because he continued to exercise in his South Beach apartment in Miami Beach into his 90s.

He said he had consulted with the director Oliver Stone on Mr. Stone’s 1995 film “Nixon.”

Mr. Martinez carried rueful memories of his covert work. The Watergate episode, after all, had ended with the group’s arrest, seized in possession of incriminating cash, gloves, lock picks, walkie-talkies and film. And it had begun inauspiciously for him, after a tense personal drama. “I had just gotten my divorce that day,” he wrote in the Vanity Fair piece, “and had gone from the court to the airport and from the airport to the Watergate.”

“I can’t help seeing the whole Watergate affair as a repetition of the Bay of Pigs,” he added. “The invasion was a fiasco for the United States and a tragedy for the Cubans.”

In an interview for a never released documentary, Billy Corben, the film’s director, recalled on Facebook that Mr. Martinez had lamented that his lifelong mission to liberate Cuba, most notably through the Bay of Pigs invasion, had failed.

“For what? They all died for nothing. We lost Cuba,” he was quoted as saying. Then, Mr. Corben recalled, “suddenly, his eyes brightened up — like he was just struck by a sweet warm breeze off the coast of Varadero — and he grinned slyly: ‘But we won Miami.’”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/biden-reinstates-aluminum-tariffs-in-one-of-his-first-trade-moves