When Edward J. Perkins was a student at a segregated school in Pine Bluff, Ark., his history teacher taught the class about the brutal racial oppression in South Africa. It was even worse, the students were told, than what they as Black people were experiencing in the American South.

The teacher urged her students to donate what little change they had to the African National Congress, in support of its struggle against white minority rule.

Dr. Perkins recalled that lesson often when he became the United States’ first Black ambassador to South Africa, serving during the last bitter decade of the system that had come to be called apartheid.

“We were Black teenagers in the middle of Arkansas, young people discriminated against ourselves, Black boys and girls who could barely find South Africa on a map,” he recalled in a memoir, “Mr. Ambassador: Warrior for Peace,” written with Connie Cronley and published in 2006.

“But,” he added, “we contributed our pennies and nickels for this noble fight.”

Ambassador Perkins died on Nov. 7 at a hospital in Washington. He was 92. His daughter Katherine Perkins said the cause was complications of a stroke.

Dr. Perkins, whose grandparents had been born into slavery, rose to the upper reaches of the State Department.

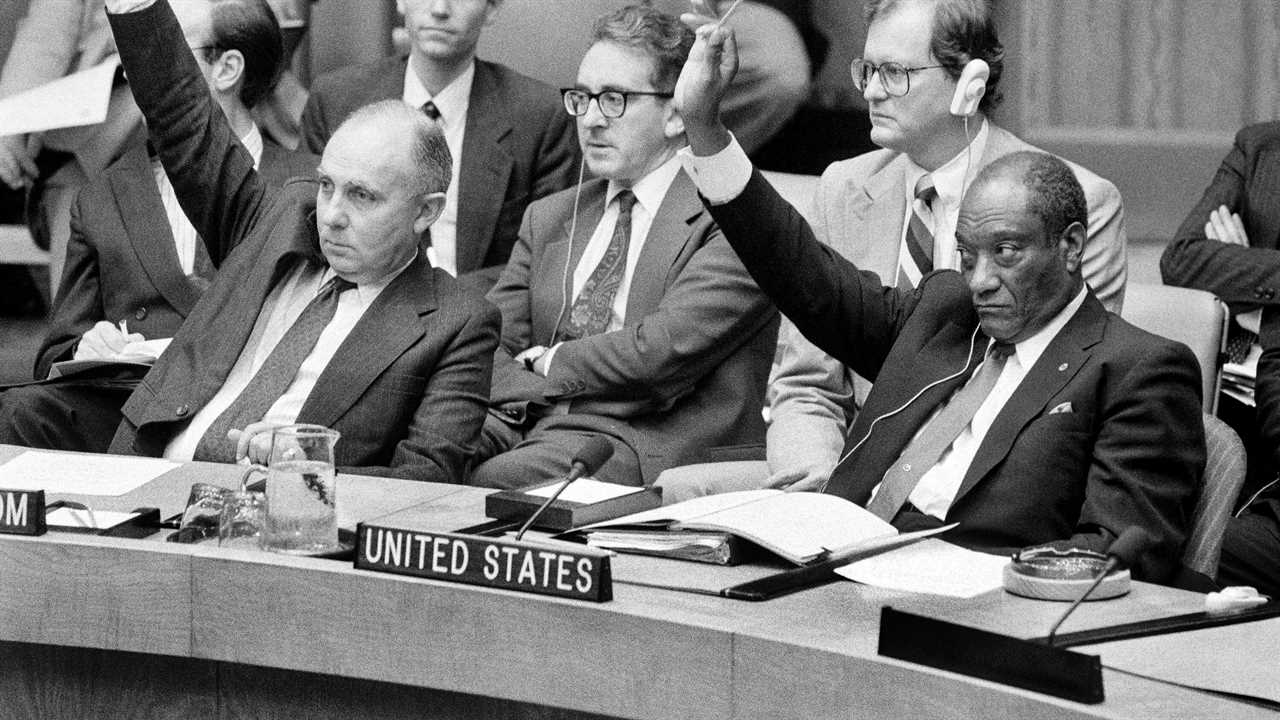

In addition to his ambassadorial postings, which also included Liberia and Australia, he became director general of the Foreign Service and helped recruit young officers from beyond the Ivy League. He became U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and in 1992 served as U.S. representative to the United Nations Security Council.

After he retired from the Foreign Service in 1996, he spent a dozen years at the University of Oklahoma, directing its International Programs Center and teaching geopolitics.

“We just lost a giant of diplomacy,” Susan Rice, who served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in the Obama administration, wrote on Twitter after Dr. Perkins’s death. “Pioneer among African Americans, champion of a diverse Foreign Service.”

In addition to recruiting people of color, women and people from places like Appalachia, Ambassador Perkins oversaw the hiring of Avraham Rabby, the first blind person in the diplomatic corps. (Mr. Rabby died in May at 77.)

His most challenging assignment was South Africa, where he was appointed ambassador by President Ronald Reagan in 1986.

The United States, like much of the world, was embroiled in a fierce debate over how to try bringing an end to apartheid. Congress had overridden a Reagan veto and imposed stringent economic sanctions.

Reagan had tried to fend off the vote by promising to impose sanctions on his own — and by appointing Dr. Perkins the first Black ambassador to South Africa.

Concerned that Reagan was naming a Black ambassador as a symbolic gesture because he did not want to confront South Africa in a substantive way, some Black leaders urged Dr. Perkins to refuse the appointment. Among them was the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the civil rights leader, who told reporters that having Dr. Perkins serve as the intermediary between Reagan and President P.W. Botha of South Africa would put him in “the same humiliating posture of asking a Jewish person to be a messenger between Hitler and a reactionary administration.”

But Dr. Perkins’s wife reminded him that as a member of the Foreign Service he had vowed to go wherever he was needed. He accepted the posting.

“Apartheid South Africa was on fire around me,” he wrote in his memoir.

When he presented his credentials to President Botha, the two instantly engaged in a test of wills.

“President Botha was standing one step above me,” Dr. Perkins, an imposing 6-foot-3 figure, wrote.

“I suspect that the ceremony was choreographed so that he would tower over me and I would look up at him,” he added, “but he is a short man and we stood looking one another straight in the eye. I was determined not to avert my gaze until he did.”

As the ambassador handed over his credentials, Mr. Botha had to look down, at which point he lost the staring contest.

Their relationship remained icy for the duration of Ambassador Perkins’s tour. He had made it clear that he intended to visit South African townships, attend church services and meet both white and Black people. Mr. Botha regarded this as interference.

“He stuck his finger in my face,” Dr. Perkins recalled of one meeting, which he said “was like putting his finger in Reagan’s face.” Mr. Botha “ranted on,” Dr. Perkins said, before storming out of the room. Despite Mr. Botha’s objections, the ambassador met with Black and white South Africans and even held integrated receptions.

He stayed in South Africa until 1989, by which time cracks were beginning to show in the country’s repressive regime. Nelson Mandela was released from prison the next year, and in 1994 he was elected the nation’s first Black president, bringing the curtain down on apartheid.

Edward Joseph Perkins Jr. was born on June 8, 1928, in Sterlington, La. His father was an evangelical minister who traveled from church to church to lead revivals. His mother, Tiny Estelle (Noble) Perkins, was a schoolteacher.

His parents divorced when he was a toddler, and he lived for a time with his maternal grandparents, who had been born into slavery and had not learned to read. In their town of Pleasant Grove, La., school ended for Black students in the sixth grade, so he moved with his mother and her new husband, who was also a minister, to Pine Bluff. They later moved to Portland, Ore., where he finished high school.

He decided to become a diplomat after attending lectures by former diplomats at a local international relations club. After high school, he was determined to see the world and joined the Army for three years. After returning to civilian life, he still longed to see the world and was eager to become more disciplined, so he joined the Marine Corps, serving for four years in Korea, Hawaii and Japan.

When he left the Marines, he took a civilian job with the Army and Air Forces Exchange Services in Taiwan, where he met Lucy Ching-mei Liu. They wanted to marry, but her parents objected to her marrying a man who was not Chinese. They eloped to Taiwan and married in 1962.

In addition to his daughter Katherine, Dr. Perkins is survived by another daughter, Sarah Perkins, and four grandchildren. His wife died in 2009.

While stationed in Taipei and Okinawa, Dr. Perkins enrolled in a program through the University of Maryland that allowed him to earn a bachelor’s degree in public administration and political science in 1967.

After a stint at the Agency for International Development, he passed the rigorous Foreign Service exam in 1971. While working in administrative jobs at the State Department, he studied at a satellite campus of the University of Southern California in Washington and earned his master’s degree in 1972 and his doctorate in 1978, both in public administration.

He always maintained that he was not bitter, despite facing hardships in the segregated South and racial obstacles along the way. In a 2007 interview with the University of Southern California, he recalled the words of his grandmother:

“You take what you’ve got and you keep on walking,” he said she had told him. “If you stop in the middle of the road, you won’t go anywhere.”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/a-fight-over-agriculture-secretary-could-decide-the-direction-of-hunger-policy