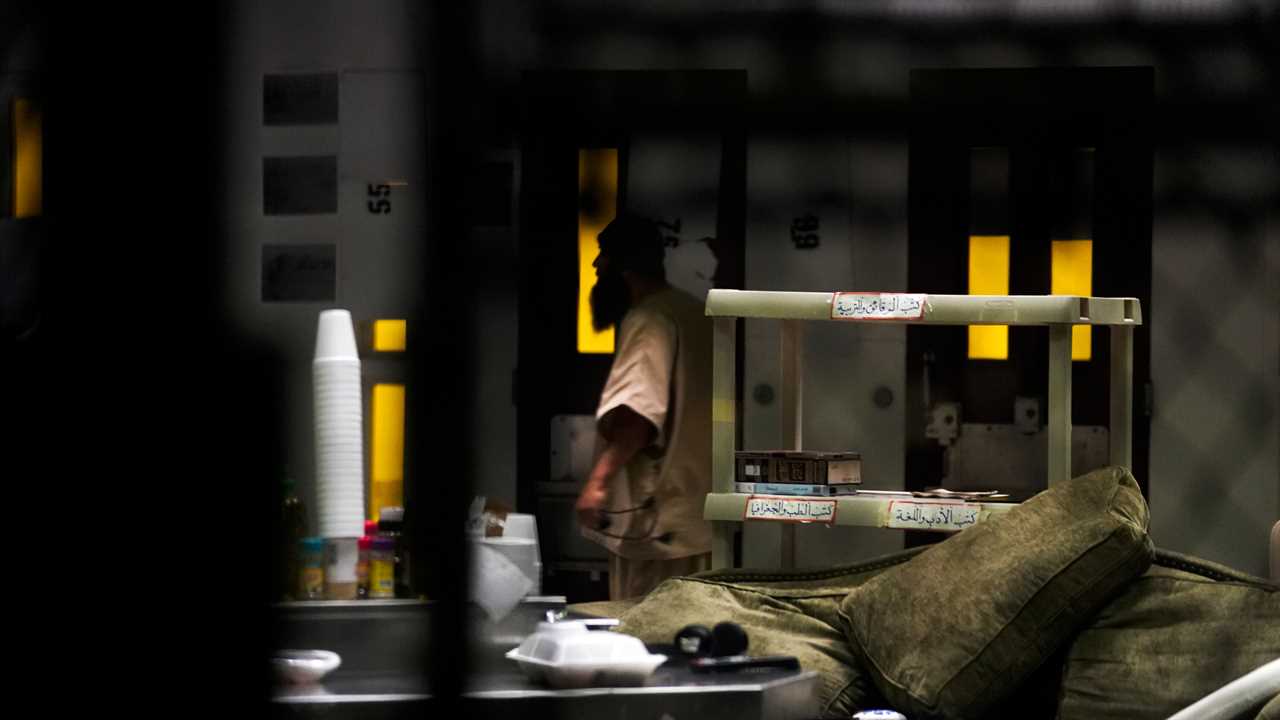

WASHINGTON — As tropical rains swamped the U.S. Navy base at Guantánamo Bay this summer and fall, raw sewage sloshed inside the cells where the military has imprisoned Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and other so-called high-value Qaeda detainees for more than a decade, the prisoners told their lawyers.

It was a problem for prisoners and guards alike. Power flickered off and on. Toilets overflowed. Water suddenly became scalding hot. Cell doors got stuck.

The descriptions dovetailed with earlier accounts by the military of failing infrastructure at the prison complex’s most secretive and highest-security facility, called Camp 7, which houses the 14 former C.I.A. detainees who were brought to the base starting in 2006 from overseas black site prisons.

The incoming Biden administration has yet to lay out plans for Guantánamo, where leftover fragments of the Bush administration’s most disputed responses to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks — indefinitely detaining terrorism suspects as wartime captives without trial, torturing them and prosecuting them in military commissions — remain unresolved three presidencies later.

President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. is not expected to repeat President Barack Obama’s splashy but ultimately unmet promise in 2009 to close the prison within a year, according to people familiar with transition deliberations. A law prohibits bringing detainees to a domestic prison, as Mr. Obama had proposed doing, and Mr. Biden said during his campaign that congressional consent is needed to close Guantánamo.

But the new administration will be forced to confront several difficult decisions, such as what to do about the building holding the 14 former C.I.A. prisoners, which is falling apart.

“Camp 7 is in bad shape, getting worse,” said Brig. Gen. John G. Baker of the Marines, the chief defense counsel for military commissions. After two weeks of quarantine at the base last month, he became the first defense lawyer to meet with a prisoner in person during the coronavirus pandemic.

“There has been maintenance done that doesn’t seem to fix things,” he said, relaying a description from a prisoner he declined to identify. “Walls are cracked. You can see light in the walls between the cells. The floor is cracked. The water is inconsistent and hot.”

One solution under consideration, according to people familiar with internal deliberations, is to close Camp 7 and move the former C.I.A. prisoners to the main prison complex while still segregating them in a special housing unit, where they would be unable to communicate with the general population of 26 lower-level detainees.

Consolidation of all 40 detainees into one site would allow the military to reduce the force of 1,500 United States service members who are deployed on nine-month tours of duty to guard them. Fewer troops would save on the cost of the operation, which has been estimated to be $13 million per prisoner per year, more than 150 times what taxpayers pay per domestic terrorism inmate.

But moving the detainees would require the approval of the C.I.A., which has a say in operations at Camp 7 through a memorandum of agreement signed in 2006 by Donald H. Rumsfeld and Michael V. Hayden, the defense secretary and the C.I.A. director at the time.

The details remain largely classified, but the role of the agency at Camp 7 has permitted the C.I.A. to control the flow of information from and about the prisoners — their memories of torture at the black sites, where they were held and by whom — through classification, segregation, surveillance and a specially trained unit of guards called Task Force Platinum.

Certain details have emerged through declassification, leaks and military commissions hearings, but some C.I.A. secrets remain.

The government treats even the location of Camp 7 as a secret, although the facility, tucked away in the hills northwest of the main compound, is clearly visible in satellite photographs.

The idea to consolidate the prisoners at one site emerged after the Pentagon abandoned an effort to replace Camp 7 with a new, wheelchair-accessible prison as part of a 25-year plan based on the assumption that, because Congress blocked the Obama administration’s plan to close the prison, some detainees would grow old and die at Guantánamo Bay.

In 2017, Congress funded a new $124 million dormitory-style barracks for about 850 prison guards, which is now being built across the street from the base McDonald’s, but repeatedly rejected a request to appropriate $88.5 million for a “high-value prison” with hospice-care abilities.

Instead, the idea is to move the former black site prisoners to separate cell blocks at Guantánamo’s main military compound of two adjacent prison buildings, called Camps 5 and 6. The compound has a clinic, including a mental health unit with a padded cell, a dental chair for the general population of prisoners and an intensive care unit with capacity to medically isolate up to four patients at a time.

Latest Updates

- Putin congratulates Biden for winning the presidency.

- ‘It was important for me to do this one thing,’ a terminally ill elector said, casting his vote for Biden.

- No, Republican attempts to organize ‘alternate’ electors won’t affect the official Electoral College tally.

Adm. Craig S. Faller, who oversees the prison at Guantánamo as the head of the U.S. Southern Command, has declined to discuss the details beyond describing consolidation as part of a “right-sizing” approach to troop deployments at the prison. “However that goes forward again will be a policy decision,” he told reporters recently.

Several other policy questions await the new administration, including how soon the State Department will resume negotiations to find secure arrangements for detainees who are approved for transfer to other countries, and whether to restore the Obama-era role of having a special envoy handle the task.

Of the 40 prisoners currently at Guantánamo, nine have been charged with or convicted of war crimes, six have been recommended for transfer with security conditions in the receiving country, and the rest remain in indefinite detention, uncharged but deemed too dangerous to release.

Under a process created during the Obama administration, those other 25 prisoners are entitled to periodic parole-like review by six national security agencies as a pathway to transfer to foreign prisons or rehabilitation programs, or resettlement in other nations with security agreements.

But the Trump administration let that process stagnate. No prisoner was cleared on its watch until it was disclosed on Thursday that after a year of consideration, the review board had approved the transfer of a Yemeni man with “robust security assurances, to including monitoring, travel restrictions and integration support.” Diplomats will now need to find a stable country willing to take him in with those conditions.

Two other Yemenis waited two and three years each for their latest determinations declaring them still too dangerous to release.

A particularly thorny policy question facing the Biden administration is whether to rethink the military commissions system setup to try the detainees who have been charged. The system has moved at a glacial pace that has rendered it all but dysfunctional.

Eight years after their arraignment, the death-penalty trial of Mr. Mohammed and four other men accused of conspiring in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, which killed nearly 3,000 people, remains stuck in pretrial hearings.

Year after year, prospects for what could be a very lengthy trial — even before years of inevitable appeals — keep receding; the latest delays, partly caused by travel restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic, mean the trial cannot begin before the 20th anniversary of the attacks.

In practice, traditional civilian courts have proved far more effective at bringing terrorists to trial and obtaining convictions that withstand appeal; but each year, Congress prohibits the transfer of detainees from Guantánamo to the mainland for any reason — not for a trial or medical care, nor to serve time on a sentence or even for execution.

Another way to resolve the case without a contested trial may be through plea deals. That, however, would mean giving up on seeking the execution of the accused 9/11 conspirators. Jim Mattis, the defense secretary at the time, fired the top lawyers overseeing the military commissions in 2018 while they were exploring the possibility of exchanging guilty pleas for life in prison.

In those talks, according to people familiar with them, defense lawyers had been seeking assurances that the defendants could serve their life sentences at Guantánamo rather than in the harsher, isolating “supermax” prison at Florence, Colo., where men convicted in federal court of terrorism crimes typically serve time.

If such a deal were ever reached, the Guantánamo prison would most likely have to remain open for decades — and the Pentagon would again be confronted with the question of whether to build a facility capable of geriatric and end-of-life health care.