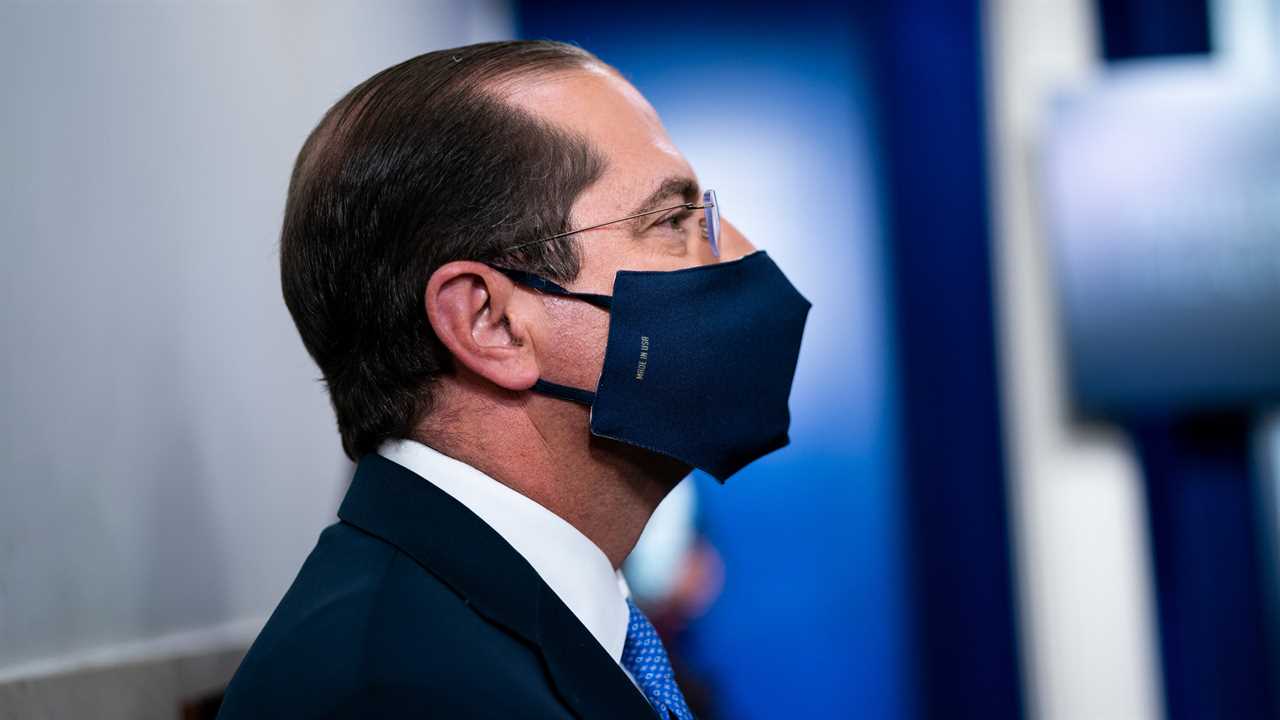

WASHINGTON — Some of the nation’s top pharmaceutical companies have stopped giving federally mandated drug discounts to hospitals and clinics that care for the poorest Americans, a move that is prompting bipartisan calls for the health secretary, Alex M. Azar II, to demand reinstatement of the price breaks or punish the firms.

The companies — including two that are partnering with the Trump administration on coronavirus vaccines — began scaling back their participation in the federal drug pricing program over the summer, saying that some hospitals and clinics were exploiting it to pad their own bottom lines. They say individual patients are not being hurt.

But hospitals, clinics and pharmacies that serve the poor say the change violates federal law and has been devastating — both to patients and to their own budgets — in the middle of an economic downturn spurred by the worst pandemic in 100 years. They say that the cutbacks are illegal and that now is not the time to reduce discounts that help them better serve the poor.

On Monday, a bipartisan group of state attorneys general, including Xavier Becerra of California, who is President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s pick for health secretary, wrote a sharply worded letter to Mr. Azar calling on him either to require the payments or impose fines on the drug makers. Twenty-eight states and the District of Columbia signed on.

“The health secretary needs to step in here and make sure that prescription drugs are provided to people that need them right now in the middle of a pandemic,” said Attorney General William Tong of Connecticut, who is leading the effort along with Mr. Becerra. “It really stuns me that companies do not seem to understand that people need access to health care and prescription drugs, literally, to live.”

A spokeswoman for Mr. Azar declined to comment, citing pending litigation. Several associations representing hospitals and clinics have sued the Trump administration, seeking to force Mr. Azar to act.

At issue is the future of the so-called 340B Drug Pricing Program created by Congress in 1992. It requires pharmaceutical manufacturers to provide steep drug discounts to certain health centers and hospitals that rely on taxpayer support — including Ryan White H.I.V./AIDS clinics and federally qualified health centers — as a condition of their drugs being covered by Medicaid.

These hospitals, clinics and their affiliated pharmacies pass the discounts on to consumers who do not have insurance, or adequate insurance, to pay for their drugs. But for insured patients, the hospitals, clinics and pharmacies are reimbursed by insurance programs at higher levels, and are supposed to use the savings to expand services to the poor.

The goal is to “stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services,” the Health Resources and Services Administration, which runs the program, says on its website.

William von Oehsen, a lawyer who represents an association of Ryan White clinics in a lawsuit against the government, described the 340B program as a “vital financing tool” and said drug companies “need to do their part to lower costs for these providers that are highly dependent on taxpayer support.”

The pharmaceutical industry, though, has never liked the program. A statement on the website of PhRMA, the industry’s trade group, declares that the program “needs to be fixed.”

Drug makers say that 340B has grown far bigger than Congress intended, costing them tens of billions of dollars each year in part because of a decision by the health resources agency about 10 years ago to extend the discounts to pharmacies that contract with eligible hospitals and health centers.

A Government Accountability Office report in 2018 found that roughly one-third of the 12,000 covered clinics and hospitals use contract pharmacies. The number of contract pharmacies has grown rapidly, the report said, increasing from about 1,300 in 2010 to nearly 20,000 in 2017.

“The statute does not contemplate contract pharmacies,” said Derek Asay, a senior adviser for government strategy at Eli Lilly, which notified the health resources agency in July that it was going to scale back its participation in the program, beginning with prescriptions for the drug Cialis, which treats erectile dysfunction.

Mr. Asay, who said the program had been “plagued with abuses and problems with integrity,” said Lilly has decided to cut off discounts for nearly all contract pharmacies. In the case of hospitals or clinics that do not have in-house pharmacies, he said, the company will make an exception to allow one contract pharmacy to receive discounts.

Latest Updates

- Nursing homes in four states are getting an early start vaccinating residents.

- A day after vaccination, these early recipients felt little more than a sore arm.

- With more body bags and mobile morgues, California braces for grim days ahead.

But Mr. Becerra — in whose lap the issue will fall should the Senate confirm him as health secretary — said in a statement that the drug makers were acting “unlawfully” in changing the program without the consent of Congress. Hospitals and clinic executives, and their lawyers, agree.

Sue Veer, the president and chief executive of Carolina Health Centers, a network of federally supported clinics, said that cutting off contract pharmacies would “reduce the savings that my health centers can retain and then invest back into primary care, things like behavioral health and substance abuse programs,” or programs for people who have H.I.V.

The move by Lilly prompted a scolding from Robert P. Charrow, the general counsel for the federal Department of Health and Human Services. Mr. Azar, who leads the department, was the president of Eli Lilly from 2012 to 2017.

In a letter sent in September, Mr. Charrow noted that the company’s stock price had jumped 11 percent since January, while “most health care providers, many of which are covered entities under section 340B, were struggling financially and requiring assistance” from the federal government. He said the timing of Lilly’s pricing changes was, “at the very least, insensitive to the recent state of the economy.”

Other drug companies — including AstraZeneca and Sanofi, both of which are partnering with the government on coronavirus vaccines — have followed Lilly’s lead, each imposing its own set of restrictions.

A spokeswoman for Sanofi, Ashleigh Koss, said that while the company “supports the 340B Program and its core objective of increasing access to outpatient drugs for uninsured and vulnerable populations,” it is refusing to grant discounts to pharmacies that are unwilling to provide data “necessary to identify and prevent waste and abuse.”

AstraZeneca said in a statement that the company “changed our approach to help mitigate the significant compliance issues that have been well documented in audits” performed by the Government Accountability Office, which audits government programs for Congress.

The companies say patients are not being harmed. But health executives and the lawyers representing them say that is not true.

In an affidavit filed in federal court as part of Mr. von Oehsen’s lawsuit on behalf of the Ryan White Clinics for 340B Access, Daniel Duck, the owner of the Corner Drug Store in Springhill, La., described a patient who paid $17.30 a month for insulin as part of the store’s “cash savings program” for customers who qualified for 340B prices.

But the cost went up to more than $1,300 after the drug’s maker, Sanofi, “no longer allowed the drug to be purchased with 340B discounts.” Eventually, the patient figured out a way to get the insulin through Medicare for a $300 co-payment, which she said she would not be able to pay the next month.

A lawyer for Equitas Health, which serves as a contract pharmacy for a federally qualified health center in Columbus, Ohio, described a similar experience involving four patients who would ordinarily pay four cents for an insulin drug made by Sanofi.

“The retail cost of the prescription is $400,” the lawyer, Trent Stechschulte, wrote in an email. Combined with a dispensing fee of $15, he said, that is a cost that patients cannot afford and a level that harms the finances of hospitals serving the poor.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/dc-passes-bill-to-give-young-offenders-chance-at-reduced-sentences