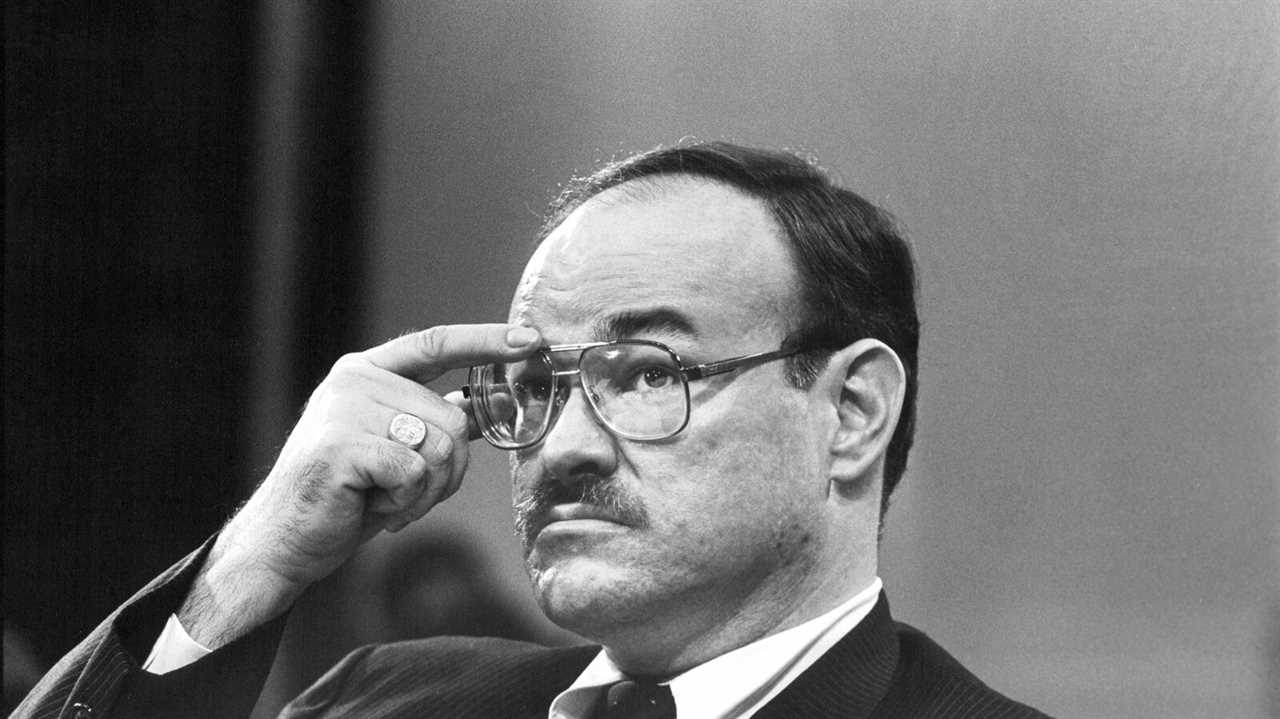

Bretton G. Sciaroni, an American lawyer who became a powerful business broker and an adviser to the government in Cambodia after being fired as a White House official when he became embroiled in the Iran-contra scandal, died on March 12 at his home in the nation’s capital, Phnom Penh. He was 69.

He had been ill for some time, friends said, but no autopsy was performed to determine the cause of death. Two fancy pens were placed in his pocket when he was buried, an honor generally reserved for senior officials.

In more than three decades in Cambodia, Mr. Sciaroni became an influential and well-connected figure in legal and business circles as well as providing the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen with legal opinions that included a justification of the prime minister’s seizure of full power in a violent 1997 coup.

That analysis and the controversy that followed it harked back to a legal opinion Mr. Sciaroni had drawn up as a 35-year-old lawyer in Washington justifying a behind-the-scenes deal in which profits from arms sales to Iran were to be used to fund the Nicaraguan rebels known as the contras, despite a law severely limiting such assistance.

That deal was orchestrated by Lt. Col. Oliver North, a staff member of the National Security Council, who told Congress he thought the two-step transaction, which became known as Iran-contra, was “a neat idea.”

Mr. Sciaroni analyzed the deal in his capacity as counsel to the Reagan administration’s Intelligence Oversight Board and found no wrongdoing.

His opinion, which he admitted to Congress was based only on brief conversations with Lt. Col. North and another official, argued that the National Security Council was not required to comply with the ban on aid to the contras.

During his testimony, Mr. Sciaroni said that he had failed the bar exam four times but had been hired by the White House on the assurance that he would take the exam again — which he did, passing it on his fifth try.

In firing him, the White House said it had not been aware that he had failed the bar exam when he was hired.

“I feel victimized,” Mr. Sciaroni said during the scandal that followed. “It’s so blatantly unfair.”

“I wasn’t a transactional person involved in this,” he said. “Congress writes a bad law. I write an opinion which is correct. I get roasted on national television. I’m sort of getting it from both ends.”

His reputation as a fast-rising star in the Republican establishment was ruined. At the suggestion of a congressional ally, he moved to Cambodia in 1993 to help the nation establish a democratic government following decades of genocide and civil war.

As one of the first foreign lawyers to arrive after a peace agreement was signed, he negotiated Cambodia’s first large-scale foreign investment deals and assisted government institutions in drafting laws and regulations.

In 1993 Mr. Sciaroni founded a law firm, Sciaroni & Associates, which facilitates and provides advice on government contracts and investment projects.

He became influential in the business world and served as chairman of the International Business Chamber of Cambodia, chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce and co-chairman of Cambodia’s Working Group on Law, Tax and Governance.

He was later formally named a legal adviser to the Cambodian government, an appointment made by royal decree that carried the rank of minister.

He angered many in Cambodia when he drew up a government “white paper” that justified a coup in 1997 by Mr. Hun Sen, arguing that his seizure of full leadership from his co-prime minister, Norodom Ranariddh, had in fact been carried out to prevent a coup.

Mr. Sciaroni was born in Los Angeles in September 1951, the son of a doctor, and grew up in Fresno, Calif.

He received a master’s degree in international affairs from Georgetown University in Washington and a law degree from the University of California, Los Angeles. He then worked for conservative policy associations before joining the Reagan administration, where he worked on arms control and commerce before moving to the Intelligence Oversight Board.

In Cambodia, according to a friend, he lived by an unchanging routine: arriving at and leaving his office early, then visiting a fixed circuit of bars, where he regularly tipped the waitresses two dollars each, a considerable sum for working Cambodians.

He called himself a devout Roman Catholic but said his regular bedside reading was not the Bible but “A Confederacy of Dunces,” a picaresque novel by John Kennedy Toole, which he opened at random before falling asleep.

He is survived by his wife, Bui Thi Hoa My; their daughter, Patricia; and two brothers.

“Brett was terrific, personally and professionally,” recalled Luke Hunt, a Phnom Penh-based foreign correspondent and columnist for The Diplomat, an online current affairs magazine. “He ranked among the handful of foreigners who genuinely knew Cambodia and the powers that made it work.”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/can-new-gun-violence-research-find-a-path-around-the-political-stalemate