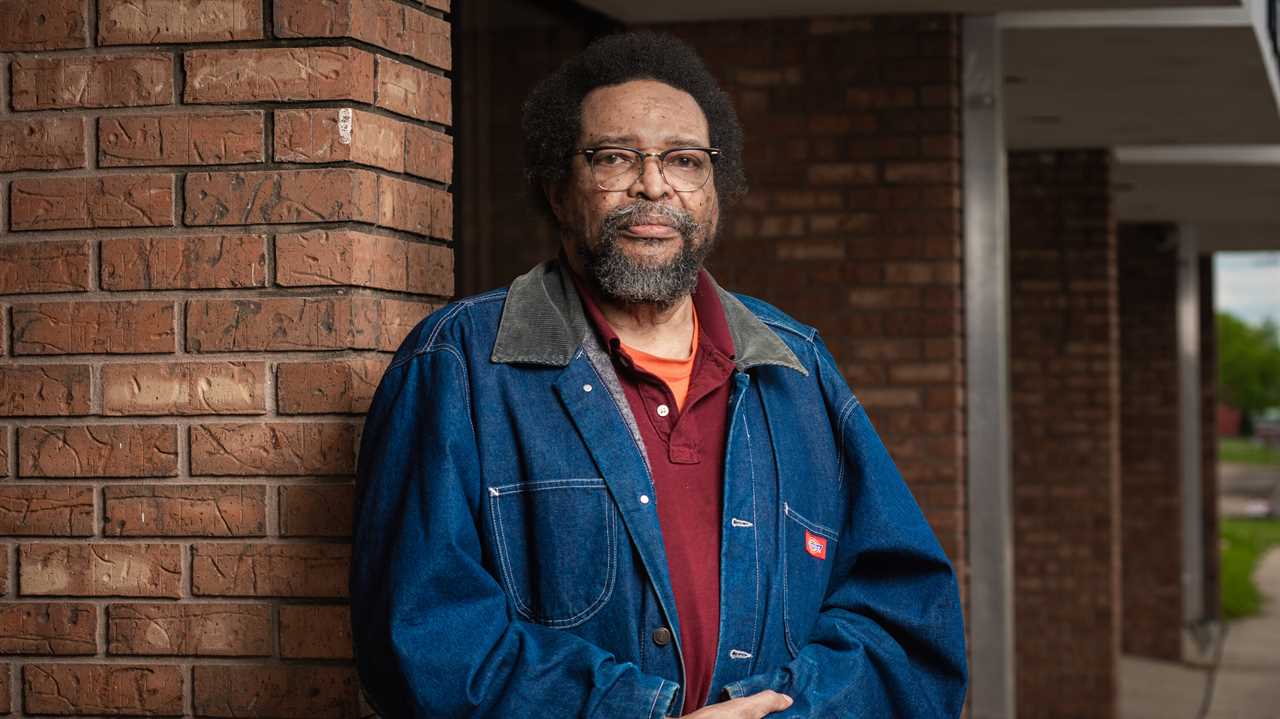

JACKSON, Miss. — The right to vote is what Frank Figgers fought for in the 1960s as a student at a racially segregated high school in Jackson, Miss. It is what Medgar Evers died for when he was shot to death outside his home in the city in 1963, after his work with the state N.A.A.C.P.

Mr. Figgers, 71, remembers learning about the assassination of Mr. Evers the day it occurred. He remembers the rage it inspired.

“When people say we’re fighting the same stuff, we really are,” he said, sitting in a local Masonic Lodge where Mr. Evers once held an office. “We were fighting in 1865 and 1965. We were fighting it in 2015 and we’re fighting it in 2021.”

Now, as Republican state lawmakers across the country push new restrictions on voting, Democrats are hitting back. In Congress, the party is pushing a colossal elections system overhaul that would take redistricting out of the hands of politicians, introduce automatic voter registration and restore voting rights for the formerly incarcerated.

For some Black Democrats in the South, the fact that this fight is happening at all — in 2021 — is a profound failure of the Democratic Party’s politics and policies. In interviews, more than 20 Southern Democrats and civil rights activists described a party that has been slow to combat Republican gerrymandering and voting limits, overconfident about the speed of progress, and too willing to accept that voter suppression was a thing of the Jim Crow past.

But Black leaders are also facing some unexpected resistance from lawmakers who fear that the sweeping bill in Congress, known as the For the People Act, would endanger their own seats in predominantly Black districts.

Republicans have often used the redistricting method to pack Black Democrats into one House district. The practice has diluted Democrats’ influence regionally, but it also ensures that each Southern state has at least one predominantly Black district, offering a guarantee of Black representation amid a sea of mostly white and conservative House districts.

Some Black Democratic lawmakers in the South have so far remained relatively muted about these concerns of self-preservation, worried that it places their own interests above the party’s agenda or activists’ priorities. Still, the doubts flared up last month when Representative Bennie Thompson of Mississippi, a Democrat whose district includes Jackson and who serves as Mr. Figgers’s congressman, surprisingly voted “no” on the House’s federal elections bill.

Recently, other Congressional Black Caucus members have urged Democratic leadership to focus more narrowly on the John Lewis Voting Rights Act — which aims to restore key parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, including the requirement that some states get federal approval before changing election laws — rather than pushing for the sweeping provisions of the For the People Act, officially known as H.R. 1.

Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., who served under Mr. Obama, said in a recent interview that Democrats were only now seeking to unify on a strategy, years after Republicans made theirs clear.

“When it came to redistricting, the Democratic response has not been nearly as polished, not nearly as concentrated, was not technologically backed in the way that the Republicans were,” he said.

Representative Mondaire Jones of New York, who was a key ally to Speaker Nancy Pelosi as she built support for the legislation, agreed with the sentiment but placed blame on the Obama administration.

“Democrats absolutely have been late to seeing the urgency of voting rights,” Mr. Jones said. “Have they not been late, we would have done something about it during the Obama administration. We needed H.R. 1 then.”

The For the People Act is set to be one of this summer’s defining clashes in the Senate. The White House will face pressure from its moderate and progressive flanks, and the act will test Senate Democrats’ commitment to the filibuster, the 60-vote threshold that has often stymied legislation in the past.

It remains unclear how far Democrats are willing to go to push through the bill, even after former President Donald J. Trump waged an open war on the results of the last election and as Republicans propose new voter restrictions in more than 40 states. Key Democratic senators like Joe Manchin III, the West Virginia moderate, have expressed skepticism about some parts of the voting bill. The House also has not yet fully passed its companion legislation, the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, or H.R. 4.

To Jackson’s tight-knit voting rights community, members of which view themselves as torchbearers in the mold of Mr. Figgers and Mr. Evers, it’s all evidence of a lingering absence of urgency.

“If the people who were most impacted by this were white people, Democrats would’ve done something about this a long time ago,” said Rukia Lumumba, the executive director of the People’s Advocacy Institute in Jackson. Her brother is the mayor of Jackson and her late father also held that role. “They thought, ‘Oh, that’s just the South,’ and not that what we’ve experienced here was coming to the rest of the country.”

Mr. Holder, who now runs a group that focuses on redistricting and ballot access, said he would encourage senators to eliminate the filibuster to pass the For the People Act, if necessary. His group and its partners plan to spend $30 million to pitch the legislation to voters in states with key senators, including Arizona, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

“The stakes are the condition of our democracy,” Mr. Holder said. “This is more than a partisan ‘who wins and who loses?’ game. If we are not successful in H.R. 1 or H.R. 4, I am really worried our democracy will be fundamentally and irreparably harmed.”

He added, “We will still have elections every two years or every four years, but they could almost be rendered close to meaningless.”

Mr. Holder has also found himself acting as something of a voting rights ambassador among Democrats: Last month, on a virtual call with the Congressional Black Caucus, he was brought in because several of the caucus’s older members had deep reservations about the For the People Act, according to those familiar with the call’s planning, a rare rift between Democratic leadership and the group often called “the conscience of the Congress.”

In fact, Representative Thompson was the only Democrat to vote against the bill in the House, reversing his stance as a previous co-sponsor. In the weeks since, Mr. Thompson has declined several requests from The New York Times to explain his vote, or to respond to constituents who say it was at odds with Southern Democrats’ rich history of defending Black voting rights.

In a short statement given to Fox News last month, Mr. Thompson said through his office, “My constituents opposed the redistricting portion of the bill as well as the section on public finances.” However, in interviews, members of every major civil rights group in Jackson expressed surprise at his vote, even if they remained deferential to his judgment.

“Of course we noticed that,” said Arekia Bennett, the executive director of the youth-led group Mississippi Votes. “But we’re not certain on his actual reasons.”

Nsombi Lambright-Haynes, who leads one of the region’s top voting rights groups, One Voice, said Mr. Thompson’s civil rights record had earned him the benefit of the doubt.

“We’re wary of talking about it because we just assume we don’t know the full story,” she said.

People familiar with Mr. Thompson’s thinking who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private conversations said the congressman’s vote reflected the larger fear among some Black elected officials that independent redistricting committees would dilute the makeup of predominantly Black districts like his own. Advocates like Mr. Holder say the concerns about keeping Black districts intact are addressed in the bill.

Mr. Jones, who is part of a wave of new congressional lawmakers who have shaken up the Black caucus, said that any worries about how redistricting affects Black districts were not ideological but generational.

“Congress is a place where members are used to and very comfortable with the status quo, so long as it benefits them electorally,” he said. “If we don’t have a Democratic majority in the Congress, it wouldn’t matter that the Congressional Black Caucus increased its membership to 70.”

In Jackson, meanwhile, the For the People Act could be the difference in restoring voting rights for those disenfranchised because of a previous felony conviction. Groups like One Voice and Mississippi Votes said they were focusing their attention on state voting restrictions, which have proliferated since the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision to remove the Voting Rights Act requirement that several states, mostly in the South, earn federal approval before changing election laws.

“In 2016, when the election results came around, the rest of the country woke up in Mississippi and we woke up to a regular day,” Ms. Bennett said. “And so for us, the fight — whether these bills pass or not — the fights continue. Because we’re in a different war.”

Republicans remain committed to a strategy of enacting voting restrictions through state legislatures. They also have a 10-year head start, given their string of down-ballot successes that continued in 2020.

In Mr. Obama’s administration, Democrats “focused our resources on the presidency, Senate, the House,” Mr. Holder said. “We think of ourselves as a national federal party, without necessarily understanding that there’s a direct connection between federal power and the makeup of the state legislatures and governors at the state level.”

He added, “Secretaries of state, Supreme Court races in the states — you know, there was just not a focus there.”

Ms. Lambright-Haynes paused when told what Mr. Holder had said.

“It’s just really, really sad,” she said. “We’re not able to see those things here.”