WASHINGTON — Christina Hayes, 34, stopped going to the doctor for treatment of her lupus when she was pregnant and working at a cable company in Michigan in 2013. She had used up her vacation days, and without paid sick leave, she worried about paying her rent and electricity bill if she took more time off.

But after her blood pressure spiked, her doctors induced labor two months early, fearing that she might have a seizure. She and her baby ended up being fine, but Ms. Hayes, now an airline gate agent in Inkster, Mich., said that having paid leave would have allowed her to prioritize her health over her paycheck.

“I would have been able to schedule doctor’s appointments better,” she said. “I might not have gone into premature labor.”

Paid leave, a cornerstone of President Biden’s economic agenda, is one of the many proposals at risk of being scaled back or left out of an expansive social safety net bill that Democrats are trying to push through Congress. Mr. Biden’s initial $3.5 trillion plan called for providing up to 12 weeks of paid leave for new parents, caretakers for seriously ill family members and people suffering from a serious medical condition. Democrats proposed compensating workers for at least two-thirds of their earnings and funding the program with higher taxes on wealthy people and corporations.

But as Democrats try to shave hundreds of billions off the overall policy package to appease moderate holdouts, paid leave could wind up shrinking to just a few weeks. That is alarming supporters of paid leave, who view this as the best chance to secure a crucial safety net for workers, particularly women.

Researchers and economists say a federal paid leave program could provide a jolt to the labor market, lifting women’s participation in the labor force and increasing the likelihood that mothers return to work after having children. Research also has shown that paid leave policies would be particularly beneficial for people of color and low-wage workers, who are among those least likely to get such a benefit from their jobs.

Only 23 percent of private-sector workers have paid family leave through their employers, and 42 percent have access to personal medical leave through an employer-provided short-term disability insurance policy, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Under the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, workers at companies with at least 50 employees can take 12 weeks of unpaid leave. The United States is the only rich country without a federal paid leave mandate for new parents or for medical emergencies.

Paid leave advocates say they have received assurances from the White House and congressional leadership that Democrats are continuing to push for the proposed program.

“We’re a critical voting bloc,” said Molly Day, the executive director of Paid Leave for the United States. “Women are not going to forget the decisions that were made now when we go to the ballot box.”

Negotiators have discussed ways to bring down the cost of the program, such as reducing the number of weeks offered or the maximum benefit an individual could receive each month, according to people familiar with the talks. Lawmakers have also discussed trimming the number of weeks initially offered, then phasing in a 12-week benefit over a decade.

Many top Democrats say they remain committed to the original paid leave plan and have urged their colleagues in Congress and the Biden administration to keep the program intact.

Representative Rosa DeLauro, a Democrat of Connecticut, said she was worried about how the program might be pared back, particularly if the benefit is phased in.

“I am concerned at how long it will take us to get to that 12 weeks,” Ms. DeLauro said. “It shouldn’t take 10 years to do that.”

Some Democrats say passing a federal paid leave program has become more crucial amid a global pandemic that has exposed the need for workers to have access to medical and sick leave without worrying about how they will pay their bills. The social policy legislation is being fast-tracked through the Senate using a process known as reconciliation.

“If we really want to achieve paid leave in the next decade, now is the only moment, through reconciliation,” Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York said. “If you want to get everyone working who wants to be working, paid leave has to be part of the strategy.”

Research on California, the first state to offer paid family leave, has mostly shown that paid leave has a positive effect on women’s wages and participation in the labor force. Nine states and the District of Columbia have passed paid leave programs.

Christopher J. Ruhm, a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Virginia, found that under California’s paid leave law, new mothers who had worked during their pregnancy were estimated to be 17 percent more likely to have returned to work within a year of their child’s birth. During the second year of their child’s life, mothers’ time spent at work increased.

“The evidence is pretty strong that we’d see favorable effects,” Mr. Ruhm said. “It’s not going to lead to a huge increase in employment or labor force participation of women, but it would be a modest one.”

Maya Rossin-Slater, an associate professor of health policy at Stanford University, said research found that policies offering up to one year of paid leave can increase labor participation among women after childbirth. Under California’s program, the biggest gain in leave-taking is seen for Black mothers, who became more likely to take maternity leave, according to Ms. Rossin-Slater’s research.

“Implementation of paid family leave can reduce inequities,” Ms. Rossin-Slater said.

Pepper Nappo, 33, a mother in Derry, N.H., said she was left alone to take care of her newborn son the day she was discharged from the hospital in 2016. She had required stitches after childbirth.

As a barber, she did not have paid parental leave, and her husband could not afford to take more than a week off from his job at a landscaping company. The family downgraded their car and limited what they bought at the grocery store but still struggled to keep up with the bills.

“If I had paid leave, we wouldn’t have been behind,” Ms. Nappo said.

Public support for paid family and medical leave is strong, but Americans tend to differ over specific policies. A recent CBS News/YouGov poll found that 73 percent of U.S. adults surveyed supported federal funding for paid family and medical leave.

Conservatives have signaled an openness to paid leave in recent years, although they have been more vocal about supporting leave for parents than for other types of caregivers or those suffering from illness. Many have also expressed concerns for small businesses. Senator Marco Rubio of Florida and Senator Mitt Romney of Utah reintroduced a proposal last month that would allow new parents to use a portion of their Social Security to fund their own leave after the birth or adoption of a child.

While larger businesses have grown open to a paid leave program, some small business groups have pushed back against a federal mandate.

Holly S. Wade, the executive director of the research center at the National Federation of Independent Business, said the group was concerned that a paid leave program would burden small employers since it would require more administrative reporting.

“While covering the cost of some of these mandates could potentially be helpful, in the way that an owner sees it, it just comes with a lot of paperwork, a lot of confusion and a lot of challenges,” Ms. Wade said.

Supporters of paid leave say they are still pushing for 12 weeks to be available immediately, but have conceded that they would accept a permanent program that would phase in the full amount over time.

“We are very cleareyed that there are going to be cuts,” said Dawn Huckelbridge, the director of Paid Leave for All. “We think there can be a meaningful program accomplished at less than 12.”

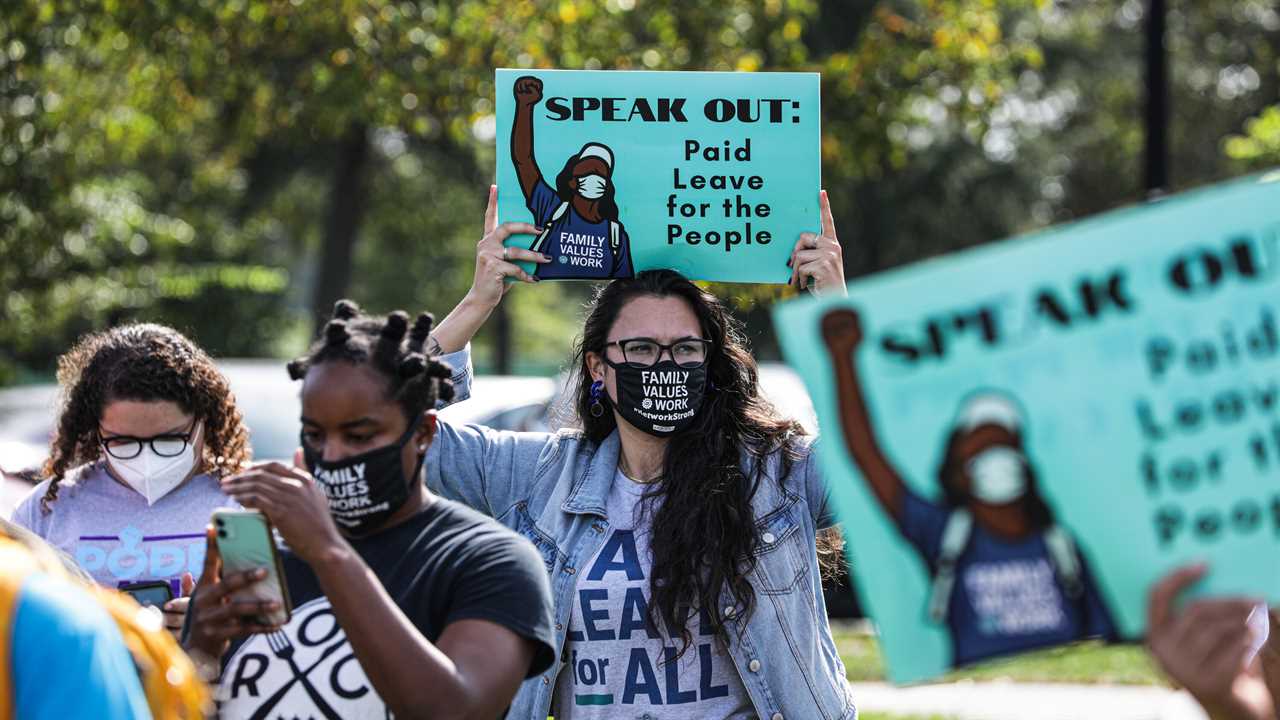

Ms. Huckelbridge and other paid leave supporters rallied near the White House last week, urging lawmakers and the Biden administration to keep the benefit in the bill.

“There have been troubling signs,” Ms. Huckelbridge said, referring to reports about demands by Senator Joe Manchin III, a West Virginia Democrat, to reduce the bill’s size and scope.