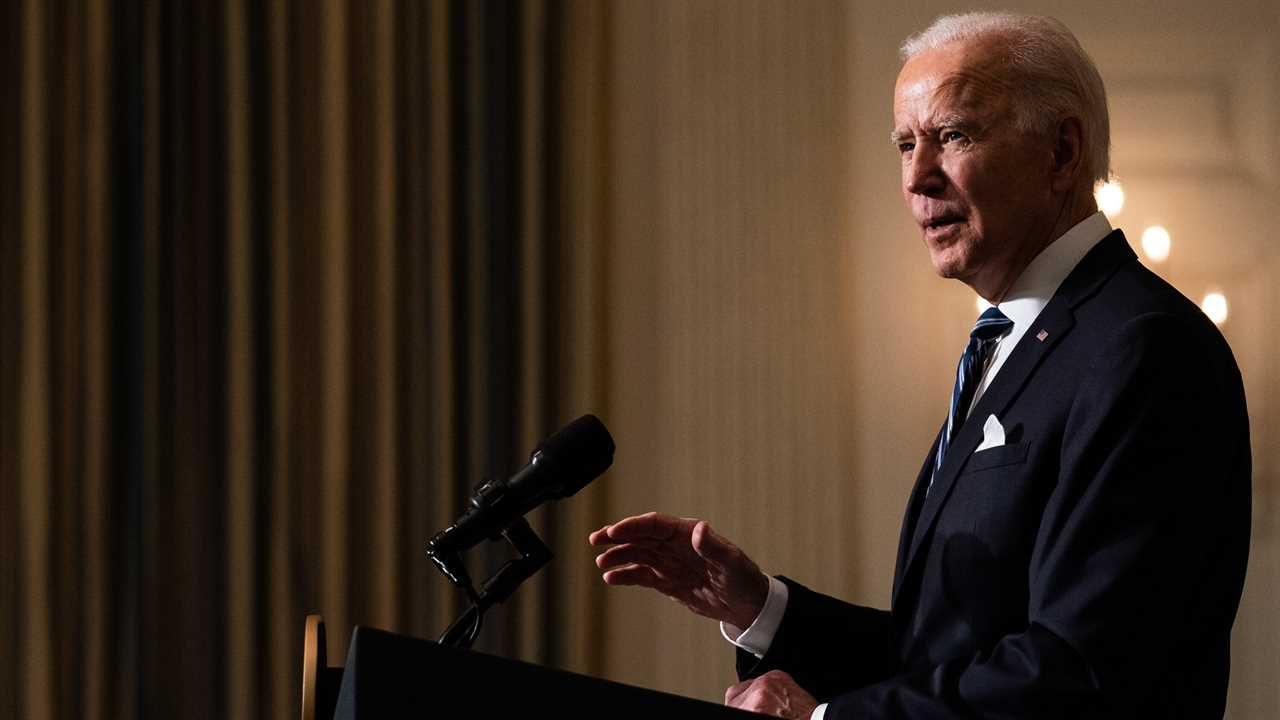

President Biden has moved swiftly in his first days to start carrying out his agenda, signing executive orders and outlining new actions meant to lift the economy, combat climate change and close the racial wealth gap. But his most significant move may in fact be a reaffirmation of an old stance — that the Senate should protect the filibuster, the 60-vote threshold that has for years stymied expansive legislation, including on issues he now seeks to address.

Progressive grumbling over the filibuster rose this week after Senator Mitch McConnell, the minority leader, initially refused to agree to basic operating rules for the chamber unless Democrats agreed to maintain the procedural tactic. But it remained just a grumble, reflecting progressives’ desire to avoid intraparty warfare early in Mr. Biden’s term and their belief, shared more widely in Washington, that his hand may eventually be forced.

Some argue that Mr. Biden, and Senate holdouts, will warm to the idea once Republicans block a popular piece of legislation, like the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, named for the civil rights hero who died last year. Others think that Mr. Biden’s desire to be seen as a transformational president will overwhelm his instincts as a bedrock Washington traditionalist.

“We have to recognize that the Senate has fundamentally changed from the time President Biden served,” said Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts, a progressive who has endorsed eliminating the filibuster. “And it’s made it impossible to move forward on big issues.”

“You cannot be unrealistically nostalgic for a time that is not coming back,” he added. “The Senate is not returning to an earlier state.”

Mr. Biden’s commitment to keeping the Senate filibuster harks back to the policy debates that animated the Democratic presidential primary. At that time, candidates including Senators Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Kamala Harris of California — Mr. Biden’s eventual running mate and vice president — either expressed openness to eliminating the filibuster or directly called for its removal.

Their logic was informed by years of congressional gridlock under former President Barack Obama and the magnitude of challenges facing the country: Big problems need big solutions, they argued, and the filibuster was a blockade to progress. Mr. Biden himself expressed some willingness to rethink his position last summer, under pressure to unite the ideological wings of the party and defeat Donald J. Trump.

“It’s going to depend on how obstreperous they become,” Mr. Biden said of Republicans at the time.

Now in office, it seems he has closed that window — a reflection of a campaign that was centered on working across party lines and his history as a Washington deal maker who was deferential to bipartisan civility.

With the Senate split 50-50 between Democrats and Republicans, that could empower Mr. McConnell and a small cadre of moderate voices to block nearly any piece of legislation. It could doom Mr. Biden to the same fate as his Democratic presidential predecessor, who blamed Republican obstructionism for blocking a more robust liberal agenda.

Mr. Markey said he was confident that if Mr. Biden began to experience the same fate, he would come around to supporting a change in Senate procedure.

“Deal with the Senate as it exists today,” Mr. Markey said. “And I believe when and if the key components of his agenda get blocked, the administration will see how much of an impediment the filibuster is.”

He added, “It’s an obstacle to progress and justice.”

Still, progressive activist groups and liberal lawmakers have largely held their fire in response to Mr. Biden’s position, responding with more of a shrug than a rallying cry. In interviews, several leaders said it was too soon to push for eliminating the filibuster. They also maintained that Mr. Biden would change his mind once his promise to “Build Back Better” faced the full reality of congressional partisanship.

Brian Fallon, the former press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign, said most activists had expected initial opposition from Mr. Biden and baked it into their strategies. He predicted that Democrats would tie an eventual all-out push on eliminating the filibuster to a widely supported bill rather than tackling the issue in a vacuum. And for certain senators — and the president — it’s important that elimination of the filibuster be seen as a last resort.

Live Updates

- McCarthy to meet Trump after rift over his assertion that the former president ‘bears responsibility’ for the Capitol attack.

- Denis McDonough, Biden’s nominee for V.A. secretary, tells Senators he’ll prioritize care access amid pandemic.

- The U.S. faces heightened threats from violent domestic extremists in the wake of the Capitol breach, D.H.S. says.

Mr. Biden’s “rhetoric remains unity-focused and conciliatory,” Mr. Fallon said. “But he’s governing in a way that makes me think that he’s putting a premium on actually getting results and making a big impact.”

Mr. Fallon added that he was optimistic that before too long, Mr. Biden and his administration would recognize the need to get rid of the filibuster.

Waleed Shahid, a spokesman for Justice Democrats, a progressive group that supports primaries against more centrist House Democrats, said the stakes for this struggle would define Mr. Biden’s presidency. His group has not sought to pressure Mr. Biden or Senate Democrats who have blocked removing the filibuster.

“We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to deliver major improvements to people’s lives, and there’s not really a way to do that without allowing the majority to govern in the Senate,” Mr. Shahid said. “Democrats really have the wind at their sails. If they don’t reform the filibuster, they could squander this moment.”

As the majority party, Democrats could move to eliminate the filibuster and force through a change to the rules on a simple majority vote — a move known as detonating the “nuclear option” — if all 50 of their members held together and Vice President Harris cast the tiebreaking vote.

But many congressional Democrats are reluctant to go that route, giving Mr. Biden ample political cover, at least for now.

Moderate Democratic senators who are central to the party’s chances of maintaining a majority — like Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona — have firmly reiterated their intention to keep the filibuster. Asked if there was any scenario that would change his mind, Mr. Manchin said, “None whatsoever.” A spokeswoman for Ms. Sinema told The Washington Post that she was “not open to changing her mind.”

Even among liberal senators, in both battleground states and safe blue seats, there is hardly the fervor for eliminating the filibuster that existed in the Democratic presidential primary. Senators Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock of Georgia, whose victories early this month delivered Democrats their dreams of united government, have largely avoided the question. Senator Dianne Feinstein of California, one of the most liberal states in the country, has frequently expressed her wariness of ending the tradition.

The minority party has often used the filibuster to thwart signature items of the majority party’s agenda, and some Democrats fear that without it, they would be powerless to stop Republicans the next time they control the Senate.

The holdouts obscure shifting political winds in the Democratic caucus, and the growing consensus among the grass-roots base that the party needs to take a strong stand on Republican obstructionism and stop holding out hope for compromise.

Faiz Shakir, a political adviser for Mr. Sanders who also worked for Harry Reid, the former Senate majority leader, said Mr. McConnell’s initial refusal to agree on operating rules might have helped opponents of the filibuster in the long run by giving Democrats an early glimpse of the opposition their agenda will face.

Mr. Shakir recounted the 2013 effort by Mr. Reid to eliminate the use of the filibuster on all presidential nominees except those to the Supreme Court, which faced an initial lack of support even among Democrats. Building consensus took time, Mr. Shakir said.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that Schumer and his staff know every Democrat who is wary of ending the filibuster,” he said. “They’re going to spend time working them.”

The desire to eliminate the filibuster was once seen as a wonky debate among Washington insiders, until Republican opposition to Mr. Obama’s agenda brought the issue to the fore. Calls to end the filibuster grew louder during Mr. Trump’s administration, when Republicans abolished it for Supreme Court nominees and confirmed Justice Neil M. Gorsuch.

In July, proponents got a major boost from Mr. Obama, who cast the tactic as a “Jim Crow relic” during his eulogy for Mr. Lewis, the Georgia congressman.

Mr. Reid, who once supported keeping the filibuster, now argues that Republicans exploited the tactic to push through an unpopular agenda. “It’s not going to hurt the Senate,” he said in a recent interview. “The Senate will be just fine. Congress will be just fine.”

Some believe Mr. Obama’s shift is a foreshadowing of the route Mr. Biden may take, though the two men come from starkly different political backgrounds. Mr. Obama was a Washington newcomer at the time of his ascension to president, though he sought to show deference to the rules of Capitol Hill. Those rules are woven in Mr. Biden’s bones, a byproduct of nearly a half century as a legislator.

Adam Jentleson, another former aide to Mr. Reid who recently wrote a book about transforming the Senate, said, “You basically have to be delusional to think that McConnell is gearing up to lead Republicans in a renaissance of bipartisan cooperation.”

He does not think Mr. Biden is.

“There’s going to be a clear choice between reform or failure,” Mr. Jentleson said. “And I have confidence that, when faced with that choice, Biden will make the right decision.”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/millions-meant-for-public-health-threats-were-diverted-elsewhere-watchdog-says