WASHINGTON — The Biden administration said Friday that it would study how it could best close the detention center at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, renewing an effort to make good on a promise made more than 12 years ago by President Barack Obama.

Emily J. Horne, the National Security Council spokeswoman, said the process would involve “close consultation with Congress,” and participation by the Defense, State and Justice Departments.

“There will be a robust interagency policy,” said Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary.

But the plan so far is short on detail. Key players have not been appointed to the task, and officials have yet to decide who would lead the effort and whether to revive the role of a special envoy at the State Department to help relocate prisoners to other countries.

Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III said as part of his confirmation process that the Biden administration “does not intend to bring new detainees to the facility and will seek to close it.”

But the White House disclosure that it would conduct an assessment of the situation, which was earlier reported by Reuters, constitutes the first public statement that it would revive the interagency process that President Donald J. Trump abandoned when he reversed Mr. Obama’s executive order intended to close the prison.

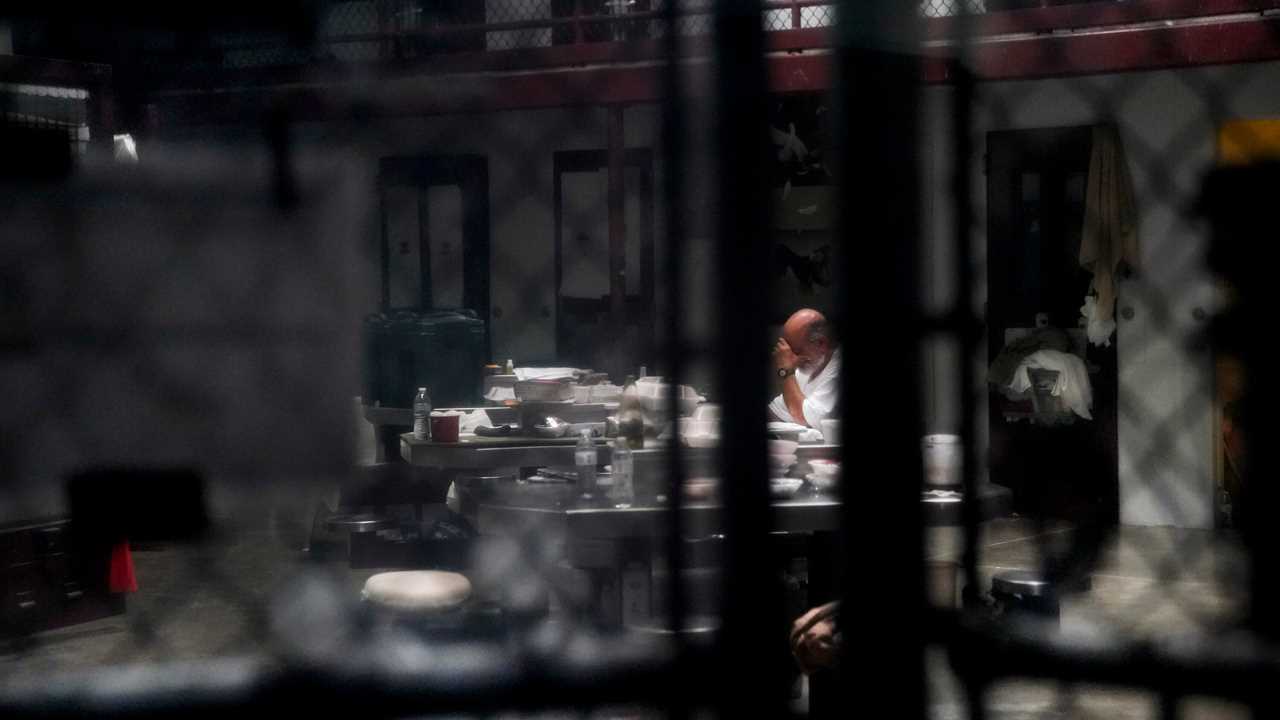

There are 40 prisoners currently at the detention center, all brought during the George W. Bush administration. The prison is staffed with an undisclosed number of contractors, civilian Pentagon employees and 1,500 U.S. troops, after a drawdown from about 1,800 troops during the Trump administration to save on costs that in 2019 exceeded $13 million per prisoner per year.

The Bush administration, which brought about 780 men and boys there, sent about 540 to other countries. The Obama administration reduced the prison population by another 200 through relocations to other nations. The Trump administration repatriated one man, a confessed Qaeda terrorist, to Saudi Arabia.

Mr. Obama’s efforts to close the prison ran into intense opposition on Capitol Hill, especially among Republicans adamant that none of the wartime prisoners be transferred to facilities in the United States. The Obama administration had determined there were a few dozen prisoners it could not safely release even if other countries were willing to take them.

Congress responded to Mr. Obama’s efforts by outlawing the transfer of any Guantánamo detainee to the United States for any reason — not for trial, imprisonment or medical treatment. Mr. Biden said as a candidate that closure would require the cooperation of Congress.

Live Updates

- Lindsey Graham will meet with Trump to discuss the G.O.P.’s future.

- Stacey Plaskett takes Trump’s lawyers to task for use of ‘clip after clip of Black women’ as part of the defense.

- Eugene Goodman, the Capitol Police officer who distracted the mob during the siege, is honored by senators.

The Justice Department will be key to any assessment of how to proceed now because a major issue will be what to do about the conspiracy prosecutions of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and four other men who are accused of helping to orchestrate the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

The coronavirus pandemic has stalled what was already slow-moving progress in the case, and the start of a trial is at least another year away. The Obama administration had sought to hold the trial in New York, but Congress’s travel ban blocked it.

A leaked Biden administration transition plan showed that the White House for a time considered an executive order that included the goal of closing the detention center. But the administration has apparently abandoned that idea in favor of what Ms. Horne called a National Security Council-led “process to assess the current state of play that the Biden administration has inherited from the previous administration.”

Representative Adam Smith, Democrat of Washington State and the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, who is a proponent of closure, said in a recent interview that he thought politicians might be more receptive to the idea of moving the last few prisoners to the United States because Guantánamo “is not a cost-effective place to detain 40 individuals.”

Mr. Smith also said that, rather than seek to close it by executive order, the administration should “build the argument and the case that this is the right policy” in order to change the law. Closing Guantánamo has become a political flash point, with supporters of keeping the prison open accusing supporters of closing it of being soft on terrorism or being willing to bring accused terrorists onto American soil.

Mr. Smith bristled at the suggestion, saying the 40 detainees at Guantánamo are no “more dangerous than the hundreds of terrorists, not to mention sociopathic murderers and pedophiles and child killers and all manner of evil who we safely incarcerate in the United States of America.”

Of those who remain at Guantánamo today, just one prisoner has been convicted of a crime, a Yemeni man who was sentenced to life in prison in 2008 for serving as Osama bin Laden’s public relations director and personal secretary. That conviction, for conspiring to commit war crimes, is under appeal.

Eleven more prisoners have been charged, six in death penalty cases. The chief prosecutor has made no effort to charge the 28 others, instead leaving them in the status of indefinite wartime detainees in an continuing conflict with Al Qaeda and the Taliban.

Six prisoners have been approved for transfers with security guarantees through various interagency reviews.

Three of the cleared men, an Algerian, a Moroccan and a Tunisian, could go home once a point person is assigned to the task of negotiating security arrangements at the State Department. But the other three require third-country resettlement because one is an ethnic Rohingya Muslim, who is stateless and has not cooperated with efforts to find him a place to go, and two are Yemenis who cannot go home because their country is embroiled in a civil war.