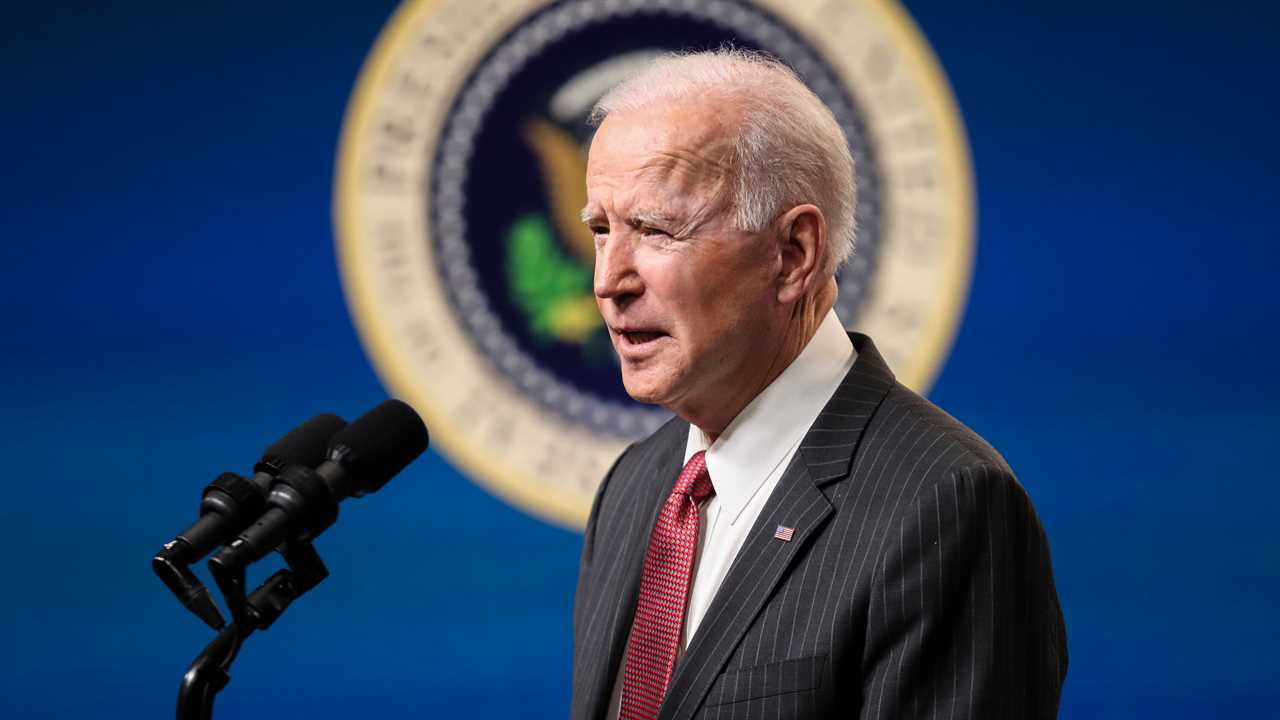

President Biden announced on Wednesday that he was imposing new sanctions that would prevent the generals who engineered a coup in Myanmar from gaining access to $1 billion in funds their government keeps in the United States, and said he would announce additional actions against the military leaders and their families.

It was the first concrete steps the U.S. government has taken since Mr. Biden demanded that the generals restore democracy and release Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the nation’s civilian leader, and other leaders, and announced that the army chief would take control.

Noting that protests are growing, Mr. Biden warned that “violence against those asserting their democratic rights is unacceptable,’’ and he said “the world is watching.” He said he had consulted with the Republican leader, Senator Mitch McConnell, and a range of nations across Southeast Asia.

But Mr. Biden’s options are limited.

Myanmar has relatively little trade with the United States, and the key partner Mr. Biden needs to join in the sanctions is China — which is building much of the isolated country’s infrastructure, including a 5G telecommunications network. And so far the Chinese have not publicly condemned the coup, or announced their own set of sanctions. If China acted, it would likely not do so with public announcements.

Administration officials have acknowledged that they have to organize the pressure campaign on Myanmar in a way that will not drive the generals further into China’s embrace.

Mr. Biden did not address that trade-off, other than to say “we’ll continue to work with our international partners to urge other nations to join us in these efforts.”

Mr. Biden has used his response to the events in Myanmar to accentuate the contrast with the Trump administration. Mr. Trump used sanctions frequently, but rarely invested much time trying to get allies to join. Mr. Trump rarely spoke about human rights violations, except when the violator was Iran, or, in his last year, China.

Myanmar, though, was a conspicuous exception. In July 2019 the Trump administration sanctioned some of the same military commanders for their roles in the atrocities carried out against Rohingya Muslims. Those included Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, the army chief who took control Jan. 31 after the party supporting the military lost a critical election.

At the time, three of his highest-ranking generals were also sanctioned, and their immediate family members were barred from entering the United States. Mike Pompeo, serving as secretary of state at the time, declared that “the United States is the first government to publicly take action with respect to the most senior leadership of the Burmese military.”

The problem is made more complex by the fact that Ms. Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate from her days as a dissident, defended the military’s actions against the Rohingya ethnic minority, and denied that atrocities, including murder, rape and arson, amounted to a genocide. The military forced more than 700,000 members of the Rohingya to flee across the border into Bangladesh, where they live in squalid refugee camps.