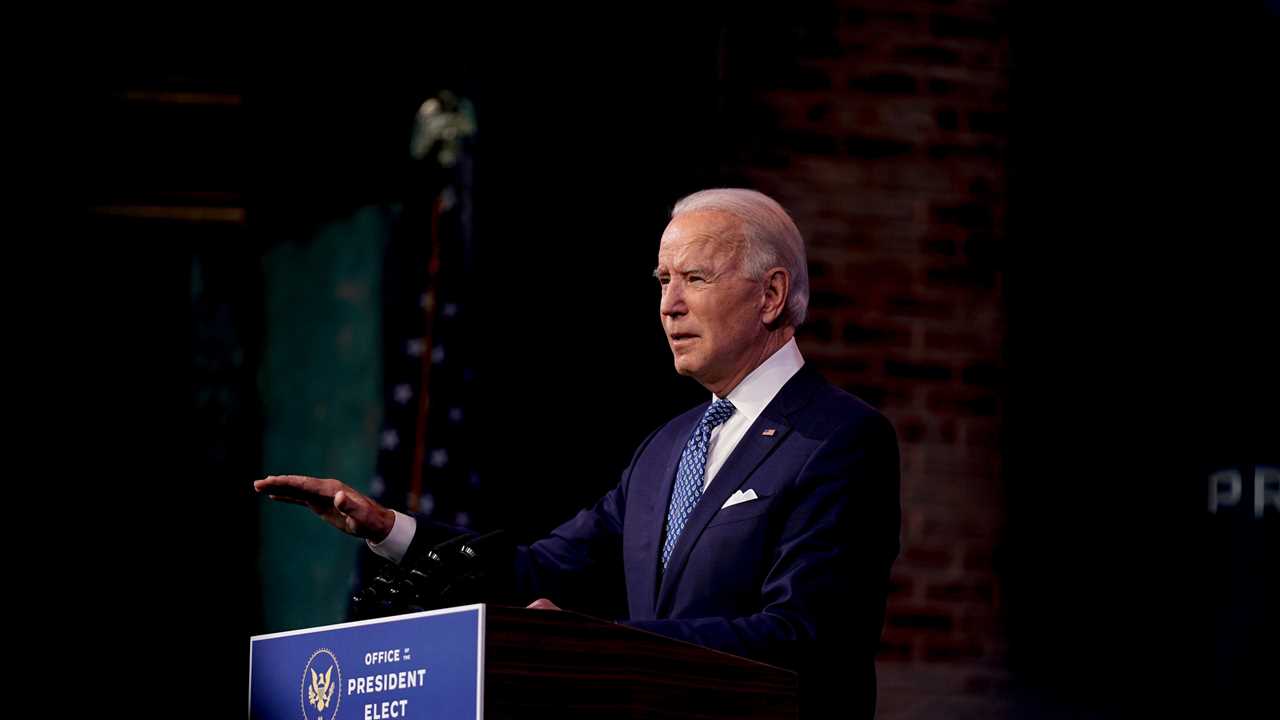

WILMINGTON, Del. — A day after Congress approved a hard-fought $900 billion stimulus package, President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. called the measure a “down payment” on Tuesday and vowed to enter office next month asking lawmakers to return to the negotiating table.

“Congress did its job this week,” he said, “and I can and I must ask them to do it again next year.”

In a year-end news conference in Wilmington, Del., Mr. Biden remained vague about the specifics of his plan. But he appeared to be laying the groundwork for how he will handle the country’s economic recovery, signaling that another major economic relief package would be a priority.

Mr. Biden said he planned to ask Congress to pass another bill that would include more funding to help firefighters, police officers and nurses. He said that his bill would include a new round of stimulus checks to Americans, but that the amount of money they contained would be a matter of negotiation.

His focus, he said, was to have the money necessary to distribute vaccines to 300 million people, to support Americans who have lost jobs because of the coronavirus pandemic and to help businesses stay open.

“People are desperately hurting,” he said.

The $900 billion package Congress approved on Monday would provide billions of dollars for the distribution of vaccines and support for small businesses, schools and cultural institutions.

It would also allocate a round of $600 direct payments to millions of American adults and children, as well as support a series of expanded and extended unemployment benefits for 11 weeks. Those programs will taper off, potentially prompting some form of congressional action before then.

“I think everybody understands that Vice President Biden is going to ask for another bill, so we will have another chance to revisit it probably pretty soon,” Senator John Cornyn, Republican of Texas, told reporters on Monday.

Mr. Biden did not negotiate with lawmakers on the stimulus directly, but his incoming chief of staff, Ron Klain, and other officials tapped to be part of the administration were kept abreast of the hour-by-hour developments in the talks, according to Democratic officials familiar with the situation.

Behind the scenes, Mr. Biden quietly pushed for lawmakers to strike a compromise that would deliver at least some modest help after months of congressional inaction. He has lavished praise on the bipartisan group of moderate lawmakers who crafted a framework over weeks of video calls, texts and huddles on Capitol Hill, helping prod leadership out of a monthslong impasse and inspiring a flurry of last-ditch negotiations.

At a November meeting in Wilmington with the top two congressional Democrats — Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California and Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the minority leader — the three leaders discussed their shared agenda, the deep policy divisions with Republicans and the additional work they planned to pursue come January.

Latest Updates

- A Florida scientist has sued state law enforcement in an ongoing battle over Covid-19 data.

- The Vatican says it is ‘morally acceptable’ to get a vaccine tied to fetal tissue.

- As the world tries to contain a new strain of the virus, questions arise about how far it has already spread.

And in drastically lowering their demands for another multitrillion-dollar package, Democrats cited the surprise success of initial vaccine trials, Mr. Biden’s victory in the election and his promise to pursue another relief package in January as part of their reason for doing so.

“Joe Biden calling this a first step, a down payment — we knew that we would revisit it, and we would have a better chance with a Democratic president who cared about science,” Ms. Pelosi said in an interview, adding that “we’ll have presidential leadership.”

But the discussions about another relief package will pose an initial test of Mr. Biden’s approach to working with Congress, and his optimism about the prospects of bipartisan legislating in an intensely polarized era. With just under a month until the inauguration, he still does not know what the balance of power will be in Congress when he assumes office, and House Democrats face a significantly smaller majority in 2021.

Even if Democrats win both runoff elections for Georgia’s Senate seats on Jan. 5 and gain control of the chamber, current Senate rules will require some Republican support to ensure that legislation clears the chamber. If Republicans hold on to at least one of those seats, Mr. Biden will be left contending with a Republican Senate majority.

In pursuing another package, he will also face the prospect of wrangling an elusive compromise on two of the thorniest policy provisions: a direct stream of funding for state and local governments, which he has repeatedly voiced support for, and a Republican demand for a sweeping liability shield from Covid-related lawsuits for businesses, schools and other institutions. With both sides so dug in on the two issues over about eight months of debate, congressional leaders ultimately agreed to remove both provisions from the final $900 billion agreement.

Republicans on Capitol Hill have begun to tacitly acknowledge Mr. Biden’s public desire for another package. But after spending more than $3 trillion this year to help the economy and struggling families, businesses and institutions, several Republicans are resistant to another sweeping package at the start of 2021.

“If we address the critical needs right now, and things improve next year as the vaccine gets out there and the economy starts to pick up again, you know, then maybe there’s less of a need,” Senator John Thune of South Dakota, the No. 2 Senate Republican, told reporters last week before the deal was reached.

Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the majority leader, has declined to commit to pursuing another round of relief, though he did not rule out another round of negotiations.

“I’m happy to evaluate that based on the needs that we confront in February and March,” Mr. McConnell told reporters on a press call on Monday. “I don’t rule it out or rule it in.”

Throughout his campaign, Mr. Biden emphasized the importance of building consensus between the two parties — a mind-set that some Democrats have dismissed as unrealistic.

But Mr. Biden, who spent 36 years as a senator from Delaware, continues to express confidence in how Republicans will work with him. He noted on Tuesday that he had faced criticism about “how naïve I am about how the Congress works.”

“I think I’ve been proven right across the board,” the president-elect said.

Mr. Biden reiterated that he believed the departure of President Trump from the White House would alter the political dynamics in Washington. “I think with Donald Trump not in the way, that will also enhance the prospect of things getting done,” he said.

Mr. Biden has plenty of experience watching new presidents try to advance their goals on Capitol Hill, and he was asked on Tuesday whether he thought he would have a honeymoon period to accomplish his aims.

“I don’t think it’s a honeymoon at all,” he responded. “I think it’s a nightmare that everybody’s going through, and they all say it’s got to end.”

Thomas Kaplan reported from Wilmington, and Annie Karni and Emily Cochrane from Washington. Nicholas Fandos contributed reporting from New York, and Glenn Thrush from Washington.