After years of court decisions battering the Voting Rights Act, a ruling in an Alabama redistricting case is reasserting the power of the 56-year-old law — and giving Democrats and civil rights groups hope for beating back gerrymandered maps.

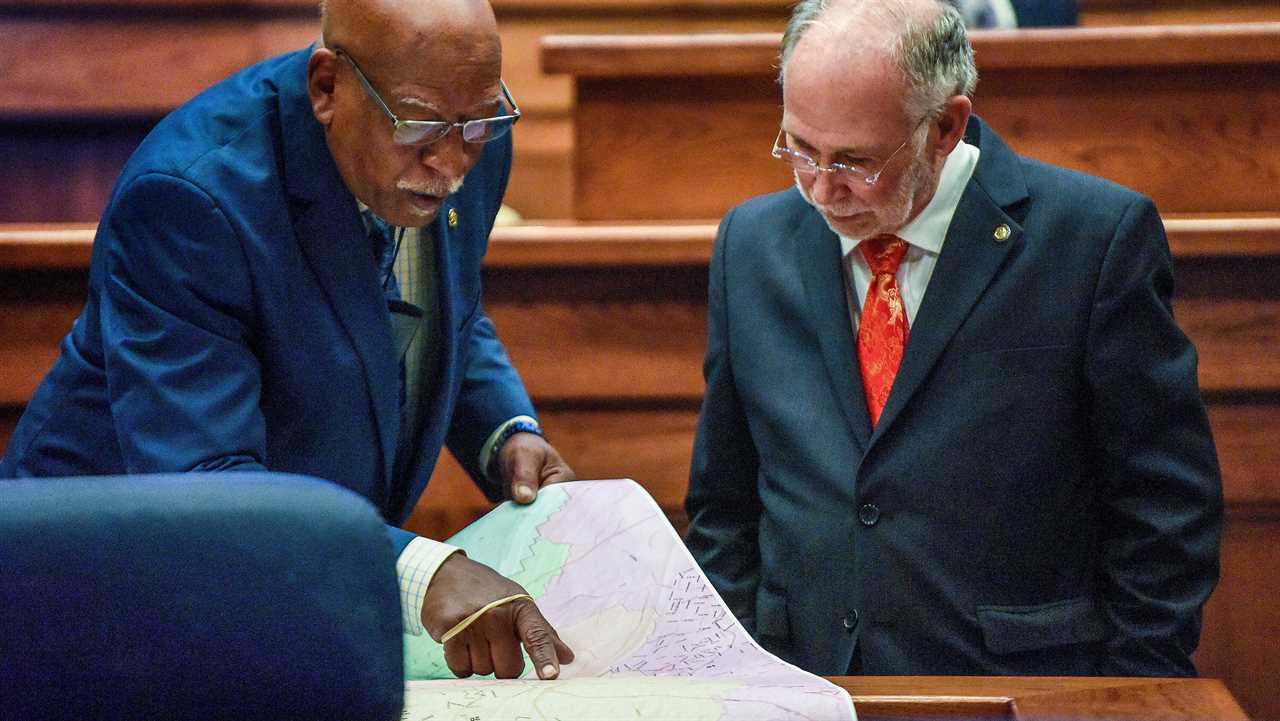

The decision from three federal judges ordered state lawmakers to rework their newly drawn congressional maps. The Republican-led legislature violated the Voting Rights Act, the judges ruled, by failing to draw more than one congressional district where Black voters might elect a representative of their choice.

Alabama’s Republican attorney general, Steve Marshall, quickly appealed the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit on Tuesday, and asked for a motion to stay the ruling.

Still, the unanimous ruling — signed by two judges appointed by former President Donald J. Trump and one by former President Bill Clinton — was a sign that a key weapon against racial discrimination in redistricting could still be potent, even as other elements of the landmark Voting Rights Act have been hollowed out by Supreme Court decisions. The case hinged on Section 2 of the act, which bars racial discrimination in election procedures.

A similar case already is pending in Texas, and the success of the challenge in Alabama could open the door to lawsuits in other states such as South Carolina, Louisiana or Georgia. It could also serve as a warning for states such as Florida that have yet to finish drawing their maps.

“The Supreme Court has cut back on the tools that we in the voting rights community have to use to deal with misconduct by government authorities and bodies,” said Eric Holder, a former U.S. Attorney General who is now the chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee. “Section 2 to now has remained pretty much intact.”

The court’s ruling in Alabama — where the Black residents make up 27 percent of population yet Black voters are a majority in just one of seven House districts — comes amid a polarized redistricting cycle, in which both Republicans and Democrats have sought to entrench their political power through district lines for congressional and legislative maps. In much of the country, that has created districts that bisect neighborhoods or curl around counties to wring the best possible advantage.

Civil rights leaders and some Democrats argue that process too often comes at the expense of growing minority communities. Black and Hispanic voters have a history of being “packed” into single congressional districts or divided up across several so as to dilute their votes.

In 2013, the Supreme Court dealt the Voting Rights Act a significant blow in Shelby v. Holder, hollowing out a core provision in Section 5. The “preclearance” provision required that states with a history of discrimination at the polls get approval from the Justice Department before making changes to voting procedures or redrawing maps. Last year, the court ruled that Section 2 would not protect against most new voting restrictions passed since the 2020 election.

Mr. Marshall, the Alabama attorney general, argued the only way to create two majority-Black congressional districts is to make race the primary factor in map-drawing and called the court’s ruling “an unconstitutional application of the Voting Rights Act.”

“The order will require race to be used at all times, in all places, and for all districts,” Mr. Marshall wrote in his appeal Tuesday. “Based on the political geography of Alabama and the broad dispersion of Black Alabamians, it is essentially impossible to draw a map like those presented by plaintiffs unless traditional districting principles give way to race.”

The case is very likely to advance to the Supreme Court, where Justice Clarence Thomas has already indicated he does not believe that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act prevents racial gerrymandering, a question the court did not address when it struck down other elements of the law.

The Alabama decision is the second this month in which a court has invalidated a Republican-drawn congressional map. The Ohio Supreme Court ruled state legislative and congressional maps drawn by Republicans violated a state constitutional prohibition on partisan gerrymandering. The North Carolina Supreme Court delayed the state’s primaries while a challenge to Republican-drawn maps there is heard.

How U.S. Redistricting Works

What is redistricting? It’s the redrawing of the boundaries of congressional and state legislative districts. It happens every 10 years, after the census, to reflect changes in population.

Republicans argued the Alabama case, along with Democratic-led lawsuits challenging GOP-drawn maps in other states, are purely efforts to add Democratic seats to Congress and state legislatures.

“This case is not about increasing minority representation, this case is about Democratic representation,” said Jason Torchinsky, the chief counsel for the National Republican Redistricting Trust. “It’s a cynical manipulation of the Voting Rights Act to get there.”

In the sweeping, 225-page opinion, the three judges undercut Republican defenses of maps that have been used in litigation across the country.

In some states where Republicans have controlled the levers of redistricting, including in North Carolina, Texas, Ohio and Alabama, legislators have stated that they did not consider any demographic data, including racial data, when drawing the maps. But the judges ignored claims that this “race blind” map drawing protects the process from claims of racial bias.

“The reason why Section 2 is such a powerful statute is because the effects test doesn’t give two figs about what your intent is,” said Allison Riggs, the co-executive director of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, a civil rights group.

Redistricting lawyers said that view could reverberate in other cases, including in Texas.

“Alabama, like Texas, tried to argue that it just didn’t look at race until after the map was fully drawn,” said Chad Dunn, a Democratic lawyer who specializes on redistricting and is involved in the Texas litigation. “That explanation is just not credible. The ostrich with its head in the sand defense in states that have an extensive history of Voting Rights Act violations is not going to work.”