How Amazon does it

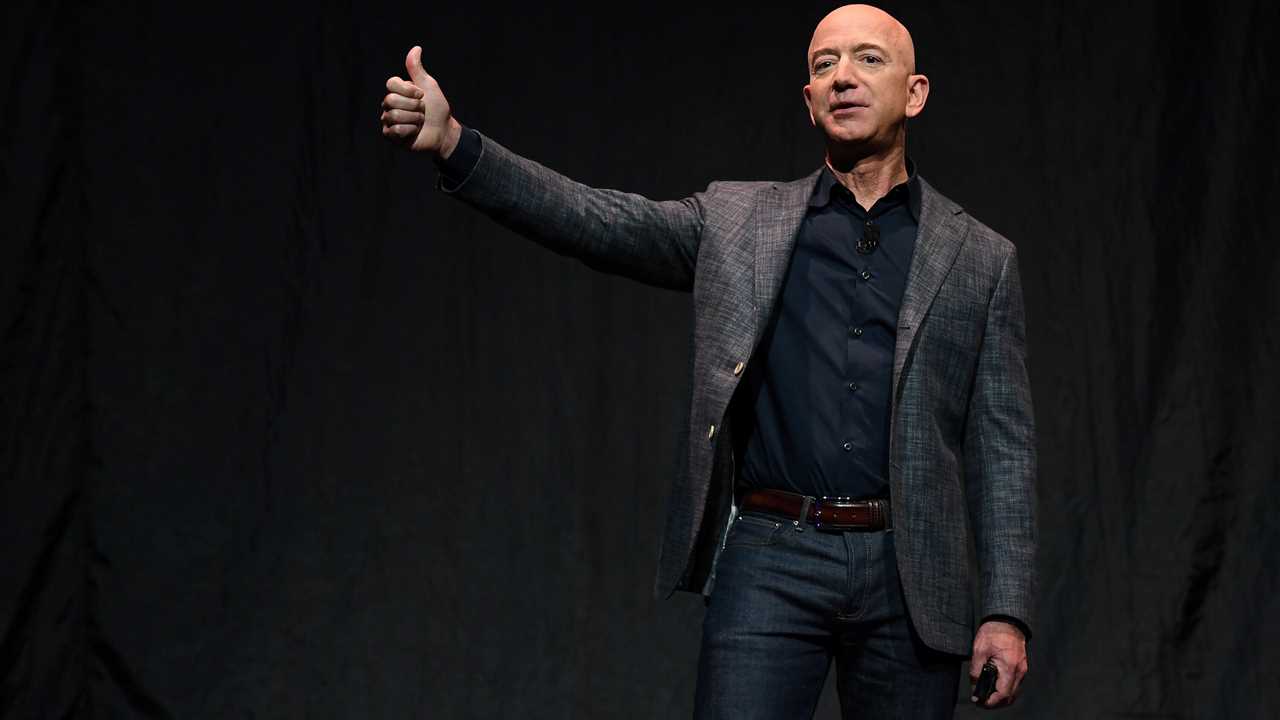

The source of Amazon’s stupefying success is only one of many mysteries — and controversies — surrounding the company that started out selling books online in 1995 and ended 2020 with nearly $400 billion in revenue, 1.3 million employees and a market value of more than $1.5 trillion. The company’s billionaire founder, Jeff Bezos, is prone to bold pronouncements about Amazon’s ambitions and opaque disclosures about where and how the company actually makes money.

Separating myth from reality in assessing Amazon’s methods has taken on a new urgency, both inside and outside the company, as it contemplates the future without Mr. Bezos at the helm. He announced this month that he would step down as chief executive this summer. So it is timely that two former Amazon executives, Colin Bryar and Bill Carr, have promised to pull back the curtain in their new book, “Working Backwards: Insights, Stories and Secrets from Inside Amazon.”

The authors say they interviewed “many Amazonians both past and present” and, based on the glowing cover blurb, appear to have had at least the tacit consent of current management. That “Working Backwards” is a lot closer to an authorized corporate profile than a tell-all, however, does not necessarily detract from its interest. Mr. Bryar and Mr. Carr each played important roles at the company during critical periods: One as a kind of chief of staff for Mr. Bezos when the Kindle and Amazon Web Services were getting off the ground, and the other started and ran Prime Video. Their portrait of Amazon’s culture and processes is fascinating and revealing, although not always in the ways they intend.

First, the authors aim to reveal the operating philosophies responsible for Amazon’s monumental achievements. Rather than offering a dull catalog of the company’s 14 leadership principles and three implementation mechanisms, Mr. Bryar and Mr. Carr provide concrete and accessible examples of how these are put into practice across a range of functions, from hiring and communications to organizational and product design. Mr. Bezos was clearly not joking when, in his first shareholder letter, he said that at Amazon, employees are not free to choose whether to work “long, hard or smart.” (It has to be all three.)

“Working Backwards”conveys the company’s exhausting focus on customer satisfaction. Many of the individual business practices described, however, are not fundamentally original. Although these often have acquired catchy Amazon-specific labels, many are simply variations on well-known Six Sigma processes and management theories, or practices developed by other companies like Toyota or Microsoft. For example, as the authors put it:

When Amazon teams come across a surprise or a perplexing problem with data, they are relentless until they discover the root cause. Perhaps the most widely used technique at Amazon is the Correction of Errors Process (COE) process, based on the ‘Five Whys’ method developed at Toyota and used by many companies worldwide. When you see an anomaly, ask why it happened and iterate with another ‘Why?’ until you get to the underlying factor that was the real culprit.

There is nothing wrong with adapting a portfolio of existing best practices, complementing them with a few of your own and then stepping on the gas. But the authors repeatedly claim that these practices both individually and collectively confer a “huge competitive advantage.” The very definition of a competitive advantage is something that your competitors cannot easily copy. If, as the authors claim, Amazon’s secret sauce is just a collection of “teachable operating practices,” they cannot constitute a competitive advantage.

Take the process singled out in the book’s title: “Working Backwards.” The idea is to start with the desired customer experience when designing new products, going so far as to draft “a press release that literally announces the product as if it were ready to launch and an FAQ anticipating the tough questions.” This process has clearly been an effective operating discipline at Amazon, but it is not a structural competitive advantage. Mr. Bezos himself has conceded that “we don’t have a single big advantage so we have to weave a rope of many small advantages.”

Second, the authors want to show how Amazonian practices were responsible for the success of some of company’s most notable products and services: the Kindle, Prime, Prime Video and Amazon Web Services.

One of the core communications practices at Amazon has been the banning of PowerPoint in favor of six-page narrative memos. Whatever one thinks about the role this has played in the company’s achievements, it has definitely made “Working Backwards” a better book. The chapter on how Amazon decided to go into the hardware business with the Kindle, in particular, is a model of clarity and thoughtfulness in chronicling the complex strategic planning and execution involved. This is how they framed it:

In physical retail, Amazon operated in the middle of the value chain. We added value by sourcing and aggregating a vast selection of goods, tens of millions of them, on a single website and delivering them quickly and cheaply to customers. To win in digital, because those physical retail value adds were not advantages, we needed to identify other parts of the value chain where we could differentiate … That meant focusing on applications and devices consumers used to read, watch, or listen to content, as Apple had already done with iTunes and the iPod.

The commitment of the book to demonstrating that Amazon’s adherence to its core principles is behind the success of these products sometimes undermines the credibility of the narrative. The company’s first leadership principle is: “Although leaders pay attention to competitors, they obsess about customers.” And so, in the book’s telling, an unexpected email from Mr. Bezos in October 2004 directing the troops to start a shipping membership program by year-end was “informed by the most basic Amazonian drive: customer obsession.”

But the authors fail to mention that an insurgent competitor, Overstock.com had started its own membership program with shipping benefits in March that year, or that Amazon’s stock at the time was faltering while Overstock’s was soaring, generating headlines like, “Is Overstock the New Amazon?” Maybe this had no impact on the company’s decision-making, but to ignore it entirely feels off.

Third, and the reason that the authors give for writing the book, is to demonstrate that “the elements of are also applicable” to achieving success in almost any endeavor, “regardless of scale and scope.” Their unspoken aim is to establish that these principles and processes do not require the charismatic leader who established them to deliver extraordinary results — a notion with sudden relevance at Amazon itself.

Even so, time and again, Mr. Bezos’ intervention, whether by introducing Prime to the opposition of all around him or personally greenlighting Prime Video pilots, seems central to the ultimate outcome. One cannot help but wonder whether it is the degree to which the collection of practices so closely reflects the ethos of the chief executive that has made them so effective. At one point, the authors actually note that certain “ways of thinking and speaking” are “distinctly Jeff-ian and therefore Amazonian.” To wit:

Jeff has an uncanny ability to read a narrative and consistently arrive at insights that no one else did, even though we were all reading the same narrative. After one meeting I asked him how he was able to do that. He responded with a simple and useful tip that I have not forgotten: he assumes each sentence he reads is wrong unless he can prove otherwise.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that the two tech giants with the strongest reputation for an obsessive focus on the culture of operating excellence — Netflix and Amazon — are those with the thinnest operating margins. Netflix’s leader, Reed Hastings, recently published a book describing its management philosophy, and the differences with Amazon are striking. For instance, Mr. Hastings believes that meetings on even the most important topics can be settled in half an hour. At Amazon, much of that of that time would be taken up silently reading a six-page memo before the debate even begins.

Yet, despite a long list of stark differences, both companies perceive themselves as cultivating compatible cultures. The point is that a wide range of operating practices can be used as forcing functions to achieve the same objectives.

None of this diminishes the magnitude of what Mr. Bezos and Amazon have achieved. On the contrary, it makes it all the more remarkable. It does, however, provide some skepticism that “Working Backwards” can be used as a simple guide for any business to achieve comparable results — or that Amazon will not need to design new principles in its post-Bezos era.

Brad Stone, the author of a best-selling history of the first 20 years of Amazon, has cited the defining characteristics of the company’s culture as being “relentless and ruthless.” He offers a more mundane theory of Amazon’s success, based on its founder’s skill for “getting the lethal combination precisely right.”

What do you think? What’s the most important thing that other companies can learn from Amazon? Will Amazon be the same after Jeff Bezos leaves? Let us know: [email protected].