Molson Hart, who runs an educational toy company in Texas, wouldn’t be as successful as he is without Amazon bringing the world’s shoppers to his doorstep.

But he’s also frustrated that the company takes so much in return and that he’s so dependent on Amazon with its complex, ever-changing decisions.

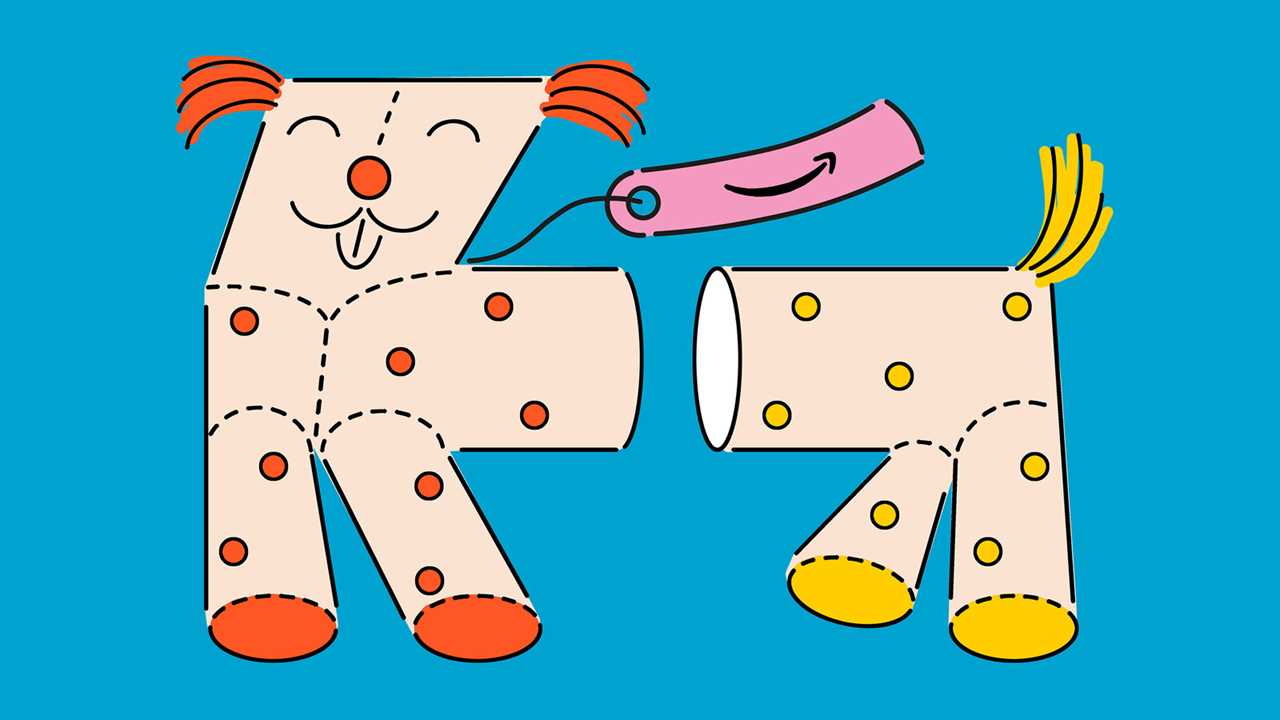

My recent discussions with Hart offered a glimpse at the often complicated feelings of those who run the companies that fill Amazon’s Everything Store. It felt as if he were describing a mostly loving but sometimes maddening relationship with a domineering partner.

One business isn’t representative of the millions of product sellers on Amazon, but Hart echoed frustrations that other merchants have expressed. I found our conversation a useful look at how a business organizes itself around Amazon and obsesses over it.

What happens to merchants like Hart’s Viahart has implications not only for what we buy and how much we pay but also for the health of the American economy.

The attraction of Amazon

I got in touch with Hart after I read his recent blog post (and a clarification) summarizing 2020 sales for Viahart, which started 10 years ago mostly selling toys in stores. Hart says that Viahart’s sales have grown from $2,000 in its first year to $7.4 million in 2020, and most of the recent growth was from Amazon. Viahart also operates its own website and sells toys on Walmart.com, eBay and other places. But 93 percent of Viahart’s sales last year were on Amazon, Hart said.

You know why. Amazon is by far America’s biggest digital mall. By selling there, Viahart doesn’t have to hunt for customers on its own.

Viahart’s figures also show that people on Amazon are far more likely to buy, not just browse, compared with shoppers on the toy company’s own website. Hart said that he assumes Amazon Prime members are conditioned to buy and know they will usually get an order fast with no additional delivery fees.

A complicated relationship

But as much as Amazon has been his lifeblood, Hart has mixed feelings.

“It’s enormously frustrating to be tied to a company that makes decisions sometimes on a whim that may be unfair or we have no control over,” Hart told me. “But I can’t complain. I mean, I do complain, but it is what it is.”

One of the more eye-opening details to me was how much it costs Viahart to sell on Amazon.

According to Hart’s figures, for every $100 worth of products that Viahart sold last year on Amazon, his company on average kept $48.25. He says that it’s far more expensive to sell on Amazon than on Walmart’s website or eBay. The cut that Viahart pays Amazon has generally increased each year, Hart says, although it declined in 2020.

Latest Updates

- Walgreens picks a Starbucks executive to be its C.E.O.

- JPMorgan plans to start a retail bank in Britain.

- AT&T now has 17.2 million HBO Max customers.

Amazon’s commission on sales — about 15 percent — is roughly the same as that of other shopping sites, like Walmart. Hart says that the costs pile on for additional services like paying Amazon to store toys in its warehouses and shipping products from there. Merchants don’t have to use Amazon’s warehouses or shipping, but the company creates major advantages for doing so.

Advertising on Amazon is optional, but like many merchants Hart says that he feels compelled to buy ads that increase Viahart’s chances of being seen.

When merchants like Hart pay Amazon or Walmart more, that often means they have to raise product prices on their customers.

An Amazon spokesperson said that the company offers many optional services for merchants, making Amazon “less expensive for the value it offers compared to other retail marketplaces.”

An ever-changing store

Hart also said that he operates at the whims of Amazon’s computer-aided recommendations, for good and bad. Around Halloween last year, Viahart experienced a big sales boost when Amazon recommended one of its stuffed tiger toys to people buying costumes related to the “Tiger King” Netflix series.

But a few days ago, Hart was frustrated that searches for Viahart’s Brain Flakes product showed the “Amazon Choice” label on a similar toy from a competitor that Viahart has sued for trademark infringement. (After he tweeted about it and I asked Amazon for comment, the label disappeared. On Tuesday, there was an Amazon’s Choice label on the Brain Flakes product.)

Hart said people shouldn’t feel sorry for his fast-growing toy business, but he wanted to draw attention to some of the downsides of e-commerce. I asked him if he would pay just about anything to sell on Amazon. He answered yes. “That is the unfortunate reality of selling toys,” he said.

Before we go …

The GARAGE DOOR OPENER is tracking you? My colleague Brian X. Chen wrote a helpful assessment of the new data collection labels for iPhone apps. And, yes, his garage door app is collecting personal information to sell ads.

Microsoft made a gazillion dollars. Again. Karen Weise digs into how the company’s products, including video games and cloud computing for businesses, were ideally suited to make $$$ during a pandemic.

Yes, there are so many streaming video services: Take the Verge quiz: Is Ovid a real streaming service? How about Xumo? Or Acorn?

Hugs to this

Happy birthday to a very large 4-year-old. Fiona the hippo celebrated with a tiered cake made with jiggly frozen fruit.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/tech-giants/what-we-learned-from-apples-new-privacy-labels