WHEN the coronavirus first hit British soil in February, most of us expected it to quickly blow over.

But ten months later, we are still on ‘stay at home’ orders unable to hug our relatives, work in the office, or gather with friends at the pub.

Boris Johnson said he believed Easter would mark a “real chance to return to something like life as normal”

The World Health Organization declared a pandemic on March 11 due to deep concerns about “the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction” globally.

The agency has refrained from giving a concise definition of a pandemic, making it hard to assess when this one will end.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the WHO, said in September: “None of us will be safe until everyone is safe.

“Global access to coronavirus vaccines, tests and treatments for everyone who needs them, anywhere, is the only way out.”

After breakthroughs in three vaccines last month, the end is finally in sight.

Many of us are hopeful for a return to our pre-pandemic lives as soon as we get jabbed.

But experts have cautioned a vaccine is not a “silver bullet”, because it is still unknown how long it will protect people, and how many will need it to gain “herd immunity”.

So what factors are needed together for the pandemic to end?

A vaccine roll-out

Without a doubt, the most desirable option to end the pandemic is an effective vaccine.

Dr Michael Head, a research fellow at Southampton University, said: “A highly-effective vaccine is essential to keep the burden of disease low and to allow us to return to some form of normality.

“If most of the population do get vaccinated, then we may see occasional small outbreaks but nothing like the scale we’ve seen across 2020.”

A vaccine works through a strategy called ‘herd immunity’; If a high enough proportion of a community is protected by vaccination, it makes it difficult for the disease to spread.

Some scientists think herd immunity is also achievable by letting the virus rip through society. But there is no hard proof that this would work, and it will mean huge loss of death.

Dr Head said: “Attempting to achieve herd immunity through natural infection would be incredibly dangerous, and thus a vaccine is the only sensible approach.

One of the vaccines that the UK has secured a deal for is from University of Oxford, manufactured by AstraZeneca

“It’s wonderful that we have a few vaccine candidates that have produced such promising results, and it’s likely we will have at least one licensed candidate available here in the UK by early 2021.”

Three vaccines from Moderna, Pfizer/BioNtech and Oxford/AstraZeneca are thought to be days away from being authorised by safety regulators after publishing results of their trials last month.

The NHS is on standby to start jabbing people, expected to be as early as Wednesday, according to the Telegraph.

But health officials have cautioned there are a number of unanswered questions about what a vaccine really means for halting the pandemic, especially given it is still not clear how well it will work at suppressing the virus.

Although all three vaccine candidates have shown to be between 60 and 95 per cent effective in interim data, this is only at preventing a person from developing the symptoms.

Prof Hunter said: “If it does have some suppressing effect on transmission, but not complete, you might still have some degree of caution. Particularly if you are vulnerable.”

He added: “We can’t say what proportion need to be vaccinated.

“It’s not like measles where you know how many need it.

“Measles vaccine lasts effectively forever. Whereas this one we don’t know, it may only last a year and people will need to be re-boosted.

“What if during that time they go on to pass the virus again? There might be people who don’t have the vaccine, because they believe conspiracy theories, who can catch it.”

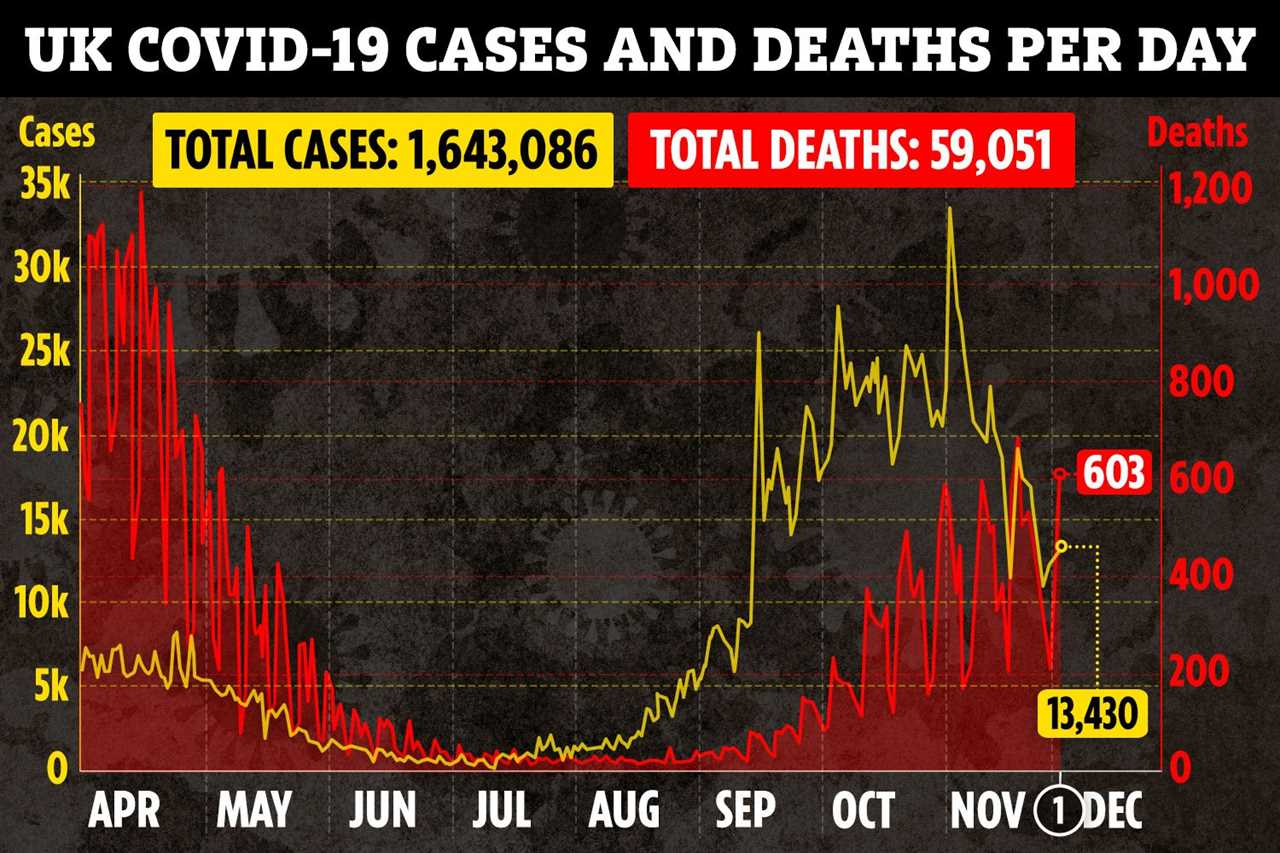

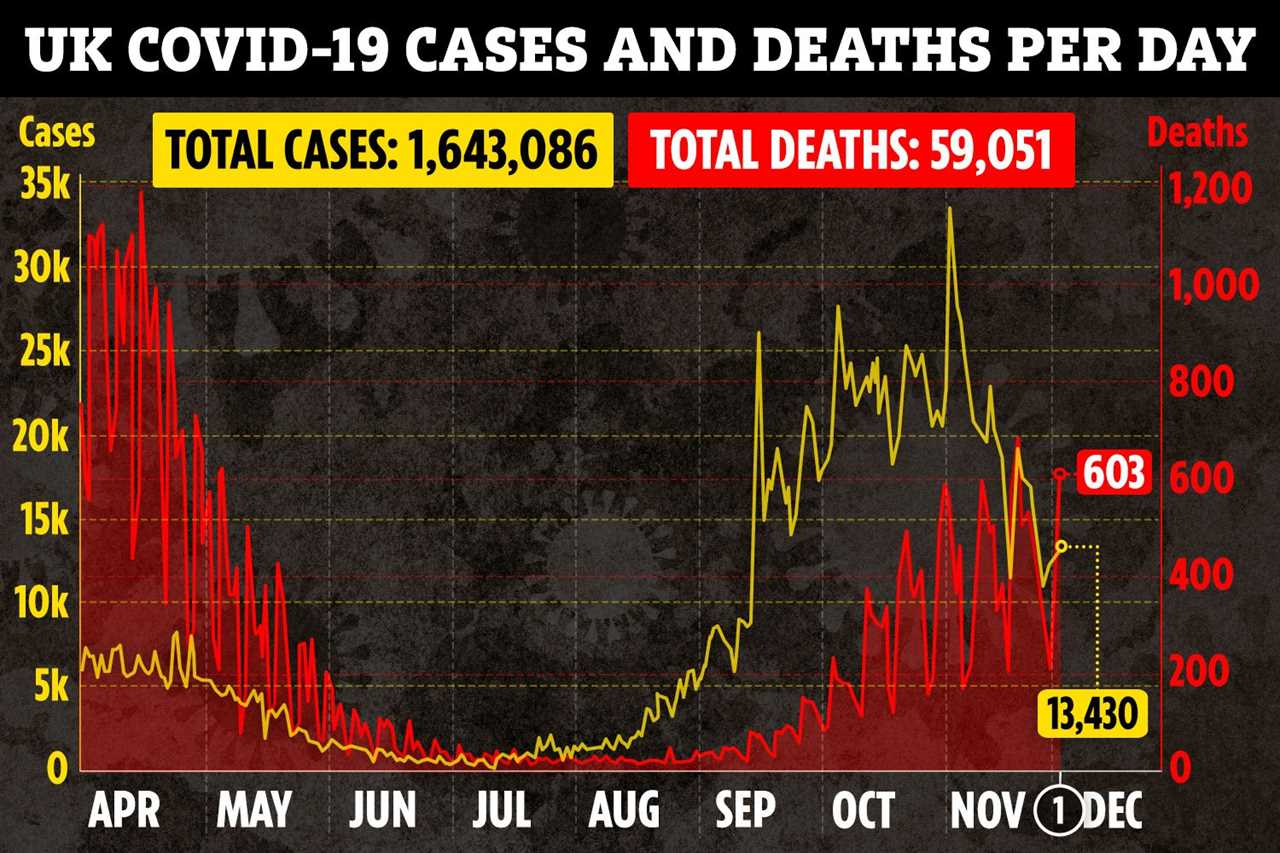

Infections and deaths must fall

It goes without saying that infection rates need to fall to low numbers in order for the Government to give us back our freedom.

Many experts and MPs – including those rebelling against the PM – believe that restrictions are too harmful to the economy.

But the Government has made it clear that their priority is getting case numbers low in order to protect the NHS, and so until then, individuals have to do all they can to limit the spread of the virus.

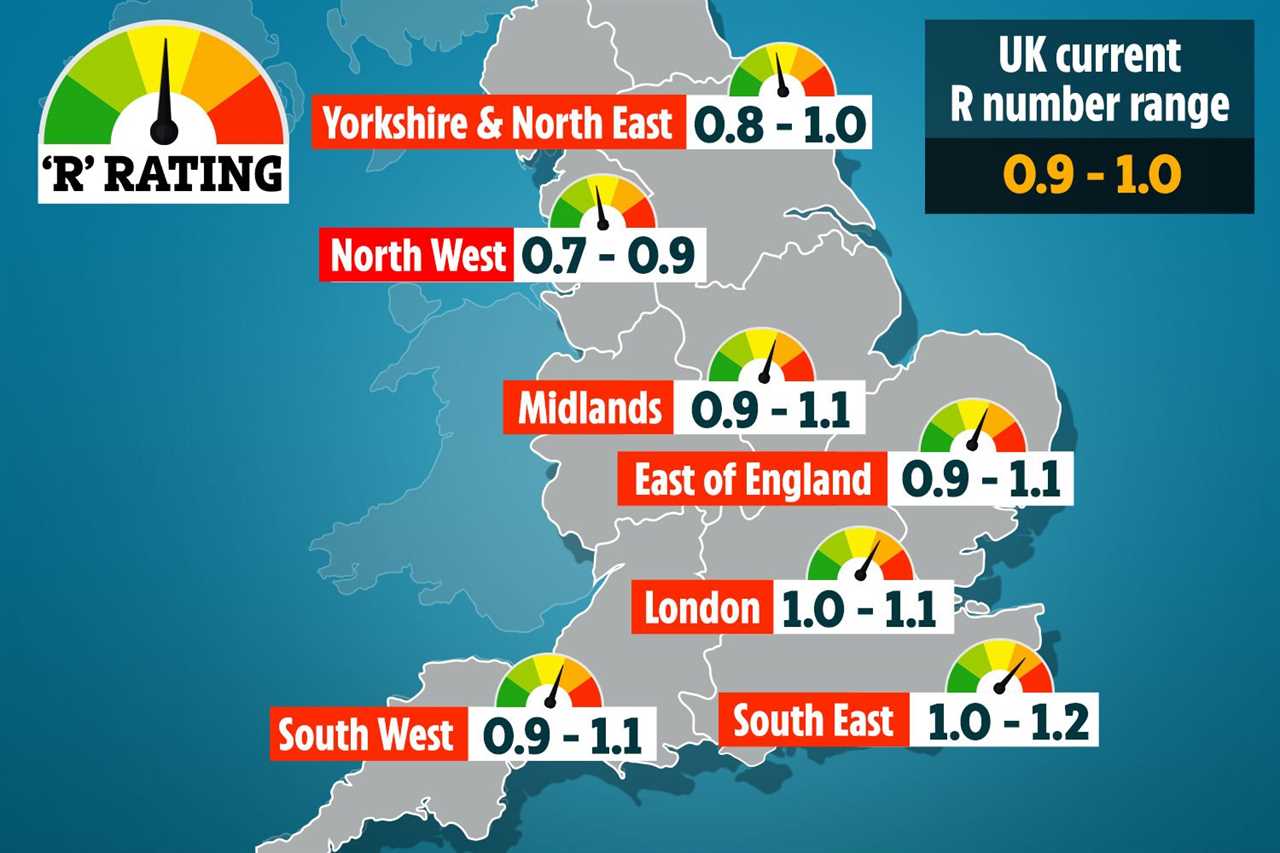

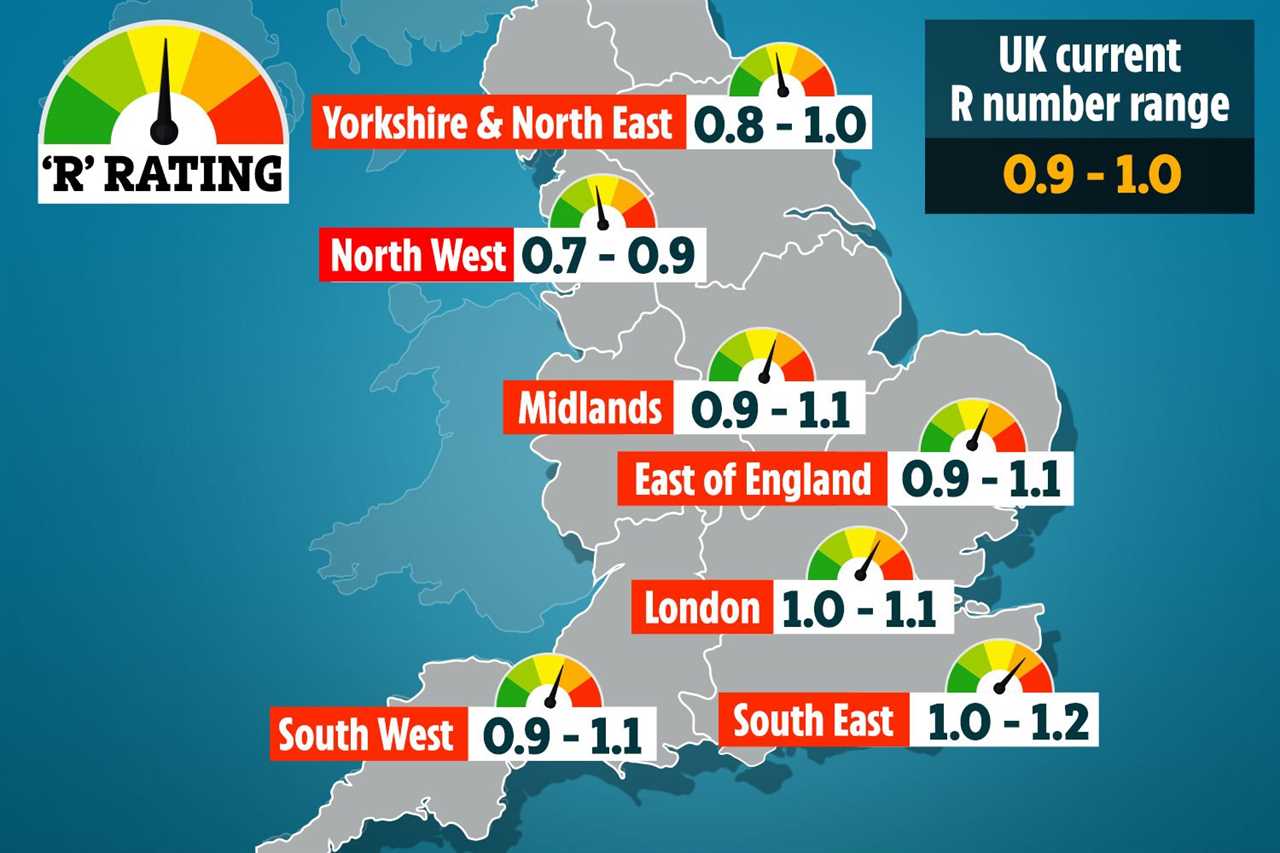

To ensure cases drop, the R value needs to be below 1.

The R value is how many people one infected person passes the virus onto. It changes depending on the behaviours of society, with limiting of social contact at schools, work and hospitality forcing it down.

Currently the R value is 0.9, according to SAGE. This means the outbreak is shrinking, but once it tips above 1 again, the outbreak grows.

When infections drop, hospital admissions and deaths follow with a two or three week lag.

The Government said on Monday without strong measures in place, the R number was likely to rise significantly above 1, leaving the NHS unable to cope.

Testing and contact tracing must be stepped up

Martin McKee, a professor of European public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and member of Independent Sage, told Trending In The News: “The highest priority is getting rates down and keeping them down with a well functioning test and trace system, and not the failing national system we have now.”

NHS Test and Trace helps limit spread of the virus by calling people who are suspected of having the virus and telling them to self-isolate before they are able to spread the virus.

But Prof Hunter said: “Test track and trace has been a big disappointment, and relatively little impact on the epidemic so far. I think that’s a real shame as it could’ve had much more value if it had been better organised from the start.

A student at University of Hull takes a swab test, November 30, before returning home this

Christmas

“However, as case numbers decrease, it’ll become easier because there will be fewer cases to track down. But I think it will become more important.”

The test and trace system, in theory, has the ability to stop a small cluster of cases from becoming a huge outbreak.

Prof Hunter said: “If those systems can really nail stopping them becoming resurget epidemic, they will have good value.”

The UK’s system failed to do this back in March because it did not have the capacity. It was relaunched in May when cases were lower.

It’s been criticised constantly for a string of failures since its launch and eve the PM has admitted it still needs improvement.

Meanwhile, rapid tests that can give results in as little as 10 minutes are part of the Government’s shift to normality.

The tests helps detect more positive cases through mass screening, particularly those that are without symptoms, and more freedom for those who test negative.

Ministers hope they will offer the return of concerts, football matches, festivals, religious celebrations and parties which have become impossible during the pandemic.

They have shown huge promise in a pilot in Liverpool, helping to drive the infection down by around six times.

But using rapid tests to get out of Covid-19 restrictions are still far from a reality in the grand scheme of things, not least because they are still in the early days of production.

On Monday evening’s Downing Street briefing, the head of operations for the programme admitted even Tier 3 areas where infection rates are highest will struggle to get their hands on the tests.

General Sir Gordon Messenger said he did not yet know how many of the 23 million people going into Tier 3 will be able to access the regime, as “planning is still very much under way”.