A MAN’S face was left paralysed and he was unable to close one of his eyes after having the Pfizer Covid vaccine.

The 61-year-old Brit suffered the side effect after both his first and second shot.

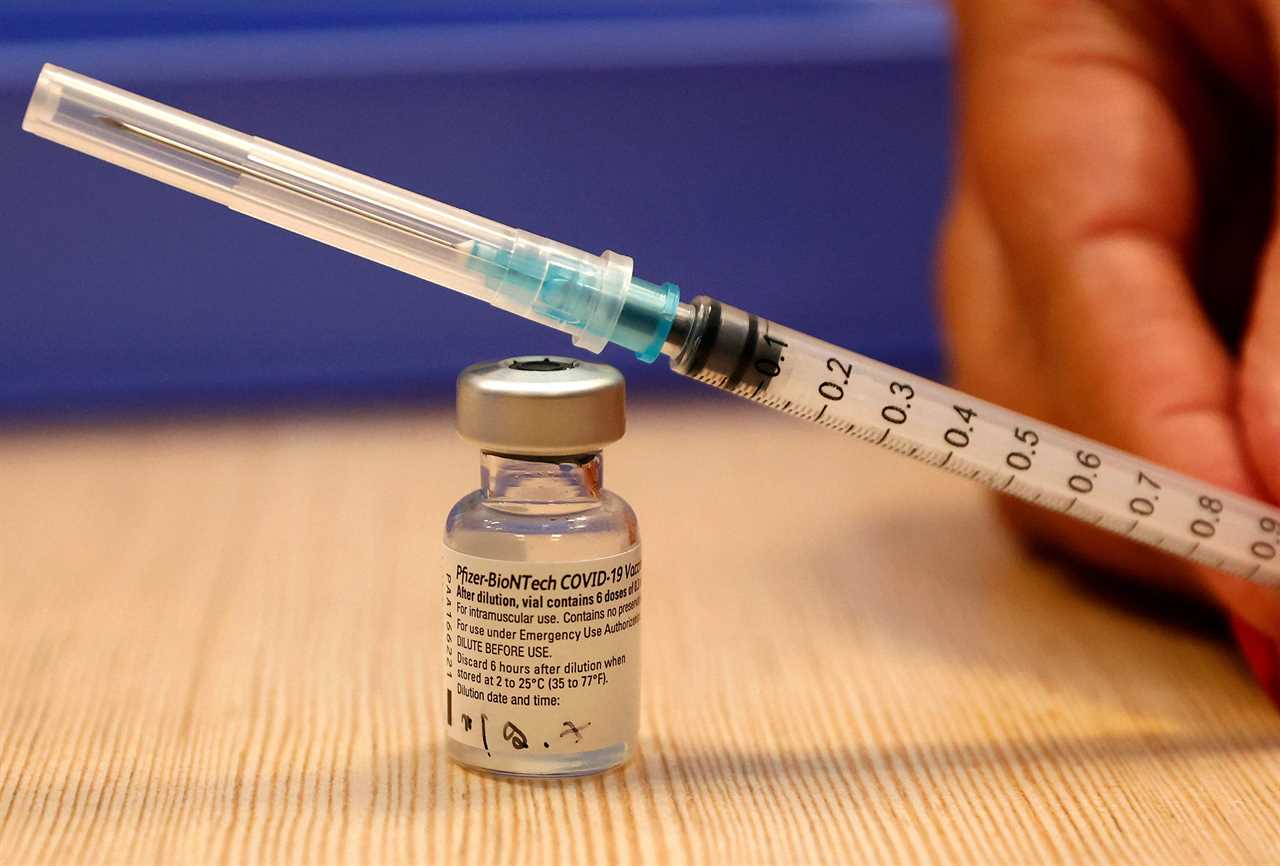

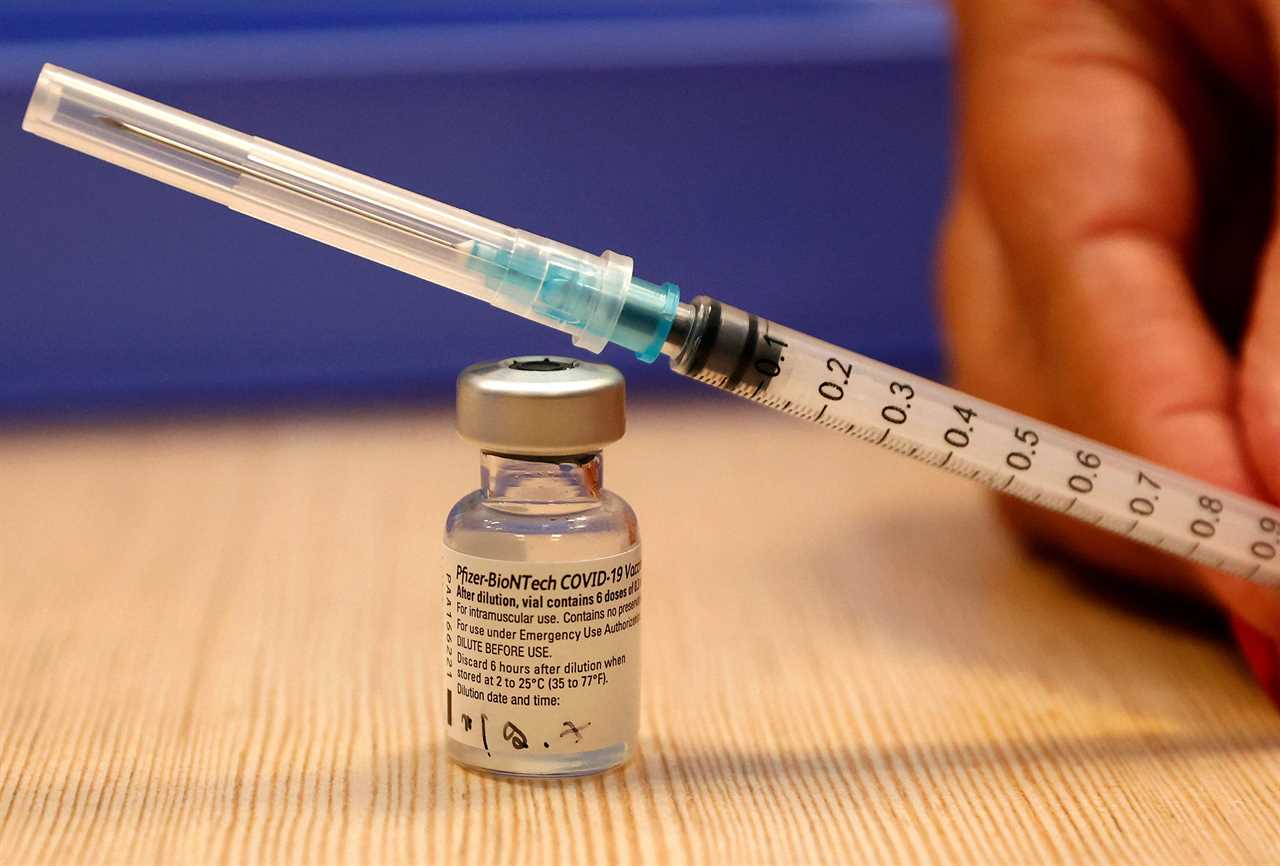

A man, 61, suffered from Bell’s palsy after both his Pfizer Covid jab doses

Therefore doctors writing in the British Medical Journal said the repeated occurence “strongly suggests” the Pfizer jab was the cause of his condition.

He was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy – temporary weakness or paralysis of the muscles in the face that can be caused by viruses.

It can be treated and most people make a full recovery in nine months. But sometimes it can take longer or be permanent, the NHS says.

It’s the first time medics have described a case with two separate episodes of face paralysis shortly after two Covid vaccine doses.

There have been occasions where people have suffered Bell’s palsy after just one jab of either the Pfizer, Moderna and Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

In clinical trials, four cases of Bell’s palsy were seen in volunteers who got the Pfizer jab, three in Moderna and three in AstraZeneca.

One person who got a fake placebo jab in the Moderna trial got Bell’s palsy, and three in the AstraZeneca study. No one in the placebo group of the Pfizer jab got the condition.

Read our coronavirus live blog for the latest updates

The case report was led by Dr Abigail Burrows, an ear nose and throat specialist at Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Guildford, Surrey.

The team described how the Caucasian man, who has been kept anonymous, first suffered the complication on the right side of his face five hours after receiving his first dose of the Pfizer vaccine.

He attended the emergency department unable to close his left eye properly or move the left side of his forehead.

A diagnosis of Bell’s palsy was given and, after routine bloods and a CT head scan showed nothing of concern, the man was discharged with a course of steroids, and the facial nerve palsy completely resolved.

He then experienced a more severe episode of Bell’s palsy on the left side of his face two days after receiving the second dose, which came six weeks after the first.

The symptoms included dribbling, difficulty swallowing and inability to fully close his left eye.

He was prescribed a course of steroids one again and was also referred to the emergency ENT (Ear Nose and Throat) clinic and ophthalmology.

The authors reported that his symptoms have greatly improved and the patient is almost back to normal.

“The occurrence of the episodes immediately after each vaccine dose strongly suggests that the Bell’s palsy was attributed to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, although a causal relationship cannot be established,” the authors said.

“Although most cases spontaneously recover with time, the symptoms can cause significant temporary disability for patients, affecting their facial expression and ability to eat and drink.

“Long-term facial weakness can lead to significant morbidity along with high rates of anxiety and depression

The man had no history of facial paralysis. But he had a high BMI, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and type 2 diabetes.

Experts agree getting vaccinated far outweighs any small risk of an adverse side effect.

There have been incidents where people have suffered a serious reaction to their Covid jab, but this has been a very small percentage of those vaccinated.

Reacting badly to any vaccination is very rare, with any side effects usually minimal.

How could the jab cause Bell’s palsy?

Bell’s palsy doesn’t have a known cause but is believed to be caused by a viral infection, such as herpes.

Other triggers may include sleep deprivation, stress, minor illness or autoimmune syndromes.

Bell’s palsy is believed to be related to facial nerve inflammation and swelling due to build up of fluid caused by a virus.

Dr Burrows and team wrote in the BMJ it was possible the jab “reactivated” dormant viral cells, leading to facial nerve inflammation.

Another theory is that vaccines could lead to Bell’s palsy through an autoimmune response, according to doctors at the Division of Infectious Diseases, Boston Children’s Hospital, US.

Dr Al Ozonoff and colleagues wrote in The Lancet in April that there was “an imbalance in the incidence of Bell’s palsy following vaccination compared with the placebo arm of each trial” of the Pfizer and Moderna jabs.

They are made using the same technology, called mRNA, while AstraZeneca and Johnson and Johnson jabs use another method.

The FDA had claimed the cases of Bell’s palsy were no higher than in the general population – which Dr Ozonoff and his team said this was incorrect.

They wrote: “The observed incidence of Bell’s palsy in the vaccine arms is between 3·5-times and 7-times higher than would be expected in the general population.”

However, the team concluded: “We feel the available coronavirus mRNA vaccines offer a substantial net benefit to public health.”

The UK’s medicine regulator, the MHRA, says: “The number of reports of facial paralysis received so far is similar to the expected natural rate and does not currently suggest an increased risk following the vaccines.”

It “continues to review cases to analyse case reports against the number expected to occur by chance in the absence of vaccination”.

There have been 313 cases of Bell’s palsy in Pfizer 31.3 million doses reported to the MHRA.

A further 14 have been seen after 1.1 million Moderna doses and 487 after 47 million AstraZeneca doses.

But reporting of a side effect does not prove cause, only that the event occurred in the period after the jab.

In 2004, a flu jab in Switzerland was found to significantly increase the risk of Bell’s palsy and was discontinued.

The side effect has been seen with other flu vaccines, but not confirmed.