THE lucky generations born since World War Two had grown to believe that our free, peaceful lives could never be tossed and turned by great global events.

And 2020 taught us we were wrong. This was the year that shook Britain — and the world — to its core.

Covid-19 came roaring out of China and had an impact on every single life in the country.

In the UK, the greatest national crisis in our peacetime history has claimed more lives than The Blitz. Nobody was untouched by the worst global health disaster for 100 years.

There have been more than 70,000 deaths. Almost two million people have caught the infectious respiratory disease, including Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who came perilously close to dying when he spent three nights in an intensive care unit in April.

And as our first coronavirus Christmas comes and goes and we deck the halls with bowls of hand sanitiser, the numbers are still rising.

Beyond the toll of the dead and infected, millions of lives have been battered and many will never be the same again.

The young saw their schools closed, their life-defining exams cancelled, their education disrupted. The old found themselves separated from their families, sometimes isolated in care homes where the virus was rampant.

Entire industries — pubs, restaurants, airlines, sport, cinema, theatres — have been mothballed, despite making heroic efforts to be safe, and many will end this turbulent year on the brink of destruction.

And in the name of the greater good, our civil liberties have been rolled up and stuffed in the attic.

There have been previously unimaginable intrusions into our freedoms as the state expanded into every corner of every life.

Spirit of real national unity

The bereaved discovered they were subject to rules on social distancing, even when their hearts were breaking.

At his father’s socially distanced funeral in Milton Keynes, Paul Bicknell moved his chair closer to his grieving mother to give her a hug and was pounced on by a council official, who separated mother and son.

State bossiness was everywhere. Many bitterly complained yet flagrant rule- breakers like Dominic Cummings, the PM’s slaphead Yoda, never really recovered from the shame.

Some state intervention was benign. Jeremy Corbyn had been widely mocked for his belief in a magic money tree but this Tory Government and their boyish chancellor Rishi Sunak — who only turned 40 this year — discovered an entire rainforest of magic money trees.

As the lockdown bit and the UK endured its worst financial recession for 300 years, Sunak fought tooth and nail to keep jobs and businesses alive, spending £300billion plus change to save our suffocating economy.

Who pays? Nobody asked. But even with Sunak’s apocalyptic largesse, there will be nearly three million unemployed by next spring.

This year was not meant to be this way. It began in a mood of upbeat optimism.

Boris Johnson had been elected with a stonking 80-seat majority last December with a mandate to get Brexit done and transform us into an independent, free-trading global nation.

The UK officially left the EU on January 31. But just one day earlier the World Health Organisation had declared a global emergency. And now we had something far bigger to worry about than Brexit. At first Covid-19 seemed too far away to touch us.

On the last day of 2019, China had reported an outbreak of Covid-19 to the World Health Organisation, most of the confirmed cases traced back to the South China Seafood Market in Wuhan, where a variety of wild animals, dead and alive, were on the menu.

Did coronavirus come from bat soup? Did it escape from a secret laboratory? The World Health Organisation jury is still out.

But from these obscure, distant and (frankly disgusting) origins sprang a virus that would inflict misery on the planet.

The British people, like their government, were slow to take Covid-19 seriously. On March 17, Sir Patrick Vallance, the Government’s chief scientific adviser, told a committee of MPs that keeping the number of UK deaths below 20,000 would be a “good result” for the country. Jaws dropped.

Less than a week earlier, when Spain had 640,000 coronavirus cases, Liverpool played Atletico Madrid at Anfield in front of 52,000 fans and Cheltenham races attracted over 250,000 spectators. We did not see coronavirus coming.

Gloomy boffins at Imperial College London predicted that the UK would be on course for 250,000 dead without the lockdown that officially began on March 23. By the end of March, hundreds were dying every day.

The fear was suddenly starting to kick in — and the great nightmare, the one that is with us still, was that the NHS would be overwhelmed by the sick and the dying.

As we finally understood that we were confronting a common enemy, there was a spirit of real national unity.

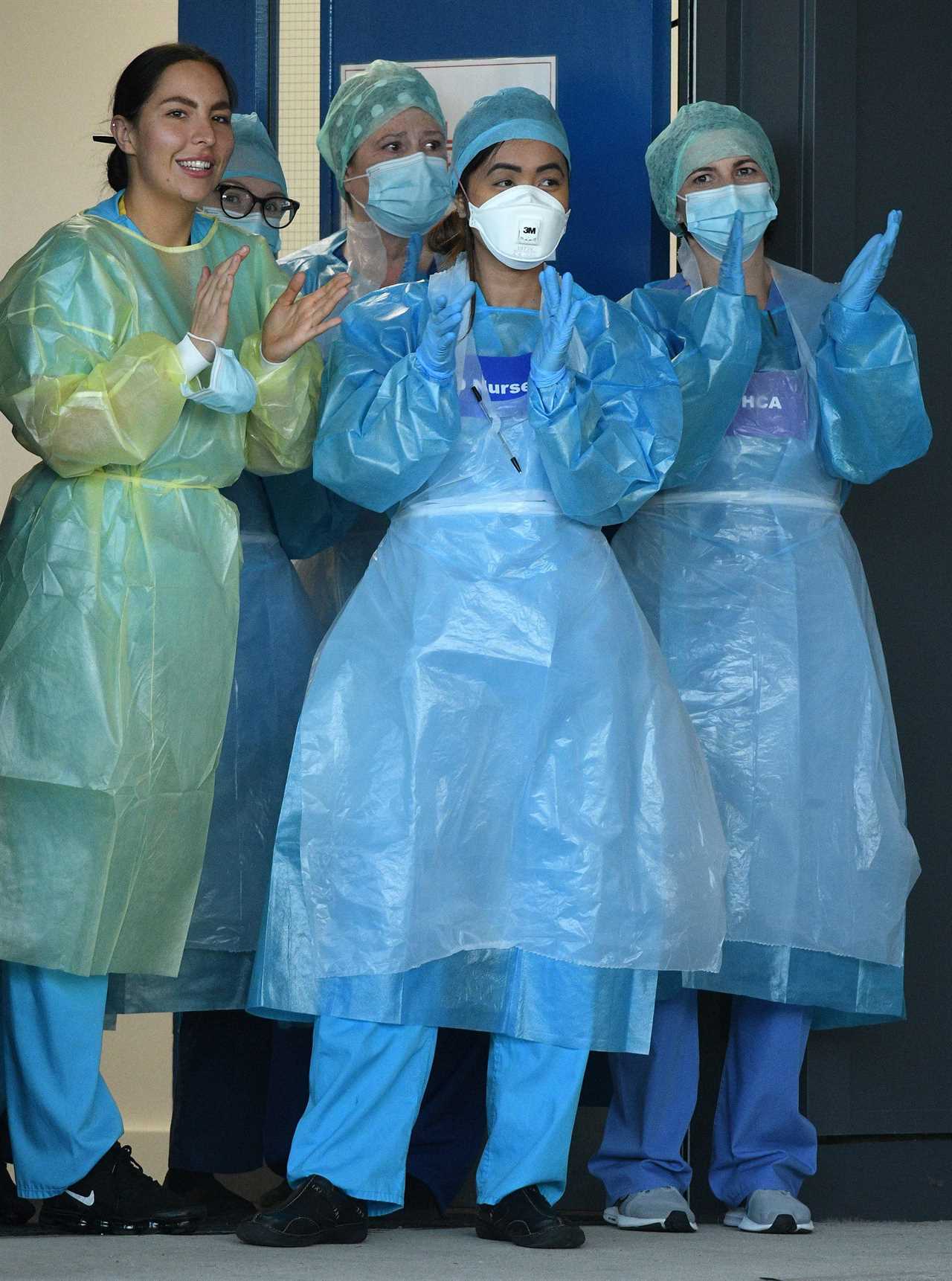

During the long lockdown of spring and summer, on Thursday nights at 8pm we stood on our doorsteps in the balmy evening and applauded the frontline heroes of the NHS. On May 8, the Queen used her VE anniversary speech to lift our spirits, and to define them.

She spoke for just four minutes and said more than Harry and Meghan will spout in a lifetime of Spotify-sponsored sermons from their California sofa.

“Our streets are not empty,” the Queen said. “They are full of love.” Many wept at her words. Aged 94, the Queen moved her nation with the simple, unsentimental yet heartfelt vow that echoed the sacrifices of 75 years ago. “We will meet again,” she promised.

It was a year for heroes. Like Captain Tom Moore, who decided to walk 100 laps of his garden in Bedfordshire to raise £1,000 for the NHS before his 100th birthday.

Before he stopped walking, Tom had raised £33million, been knighted and was on the cover of GQ mag, wrapped in the Union Jack.

Manchester United’s Marcus Rashford, a recipient of free school meals during his childhood, joined forces with the charity FareShare to deliver food to children in the Greater Manchester area who were no longer receiving free meals.

Rashford’s campaign went nation- wide, helped millions of children and, without ever raising his calm, gracious voice, he caused a major government U-turn on its free school meals policy.

And there were heroes whose names we will never know.

High street decline

Bin men. Drivers of buses and delivery vans. White van grafters who never had the luxurious option of working from home.

But our national unity became torn and frayed as the year wore on. As every effort was thrown at defeating the virus, as our economy and our freedoms were sacrificed in the war on Covid-19, many worried about the countless victims who never appeared on government statistics. The cancer patients who went undiagnosed, the heart attack victims, the clinically depressed. What was the collateral damage of lockdown? How many lives were lost “protecting the NHS”? What was the true price of lockdown?

And was it worth it?

Statistics were no longer sacred and increasingly open to debate.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock ordered a review into how Public Health England counted Covid-19 deaths after it appeared to be using Diane Abbott’s pocket calculator.

“You could have been tested positive in February, have no symptoms, then be hit by a bus in July and you’d be recorded as a Covid death,” revealed an anonymous source in the Department of Health.

There was a mounting frustration with the Government’s stern edicts, especially when they seemed to change with the weather. Rishi Sunak’s Eat Out To Help Out scheme was spectacularly popular in August but by December almost every restaurant in the country was closed, including venerable restaurants like Wiltons in London that had stayed open during the worst of The Blitz.

The hospitality sector accounted for just three per cent of coronavirus cases in October yet was forced to close down. But you were far more likely to catch Covid-19 in a hospital than in a restaurant or pub. Sometimes the rules seemed mindless.

The Government’s fixation with crushing Covid-19, whatever the cost, seemed steered by a Prime Minister understandably shaken by his near-death experience of the disease. But what you never heard anyone say was that Keir Starmer or Jeremy Corbyn would be doing a better job. There was a theory we went from 2020 to 2030 overnight. Changes already happening in our society were massively accel-erated, such as the decline of the great British high street and the rise of Amazon, the giant digital marketplace that threatens to replace everything from the supermarket to the corner shop to the shopping mall. Every high street in the land recalled Ghost Town by The Specials.

Will face masks become as ubiquitous in the UK as they are in Asia? Is working in an office a thing of the past? Will we ever be truly safe again? Will pubs reopen? Has Netflix and Amazon Prime replaced your local cinema for ever?

My local newsagent closed after a century or so. What does that say for the future of the most vibrant newspaper industry in the world? Things we took for granted for all of our lives — foreign holidays, sitting in a packed stadium to watch our team or favourite band, going to the cinema to watch the new James Bond — now seem horribly out of reach as the year draws to an end. Will they return?

There was a great retreat into the home and it feels that the free, open, fresh-air world that we all grew up in has been lost forever, in ways that are yet to reveal themselves. Cash, handshakes and social kissing have probably all had their day.

For years the Brexit debate had raged about what national sovereignty means in the modern world. But with a global pandemic across five continents, 2020 was the year when we were undeniably connected to the rest of the planet.

A 46-year-old black man called George Floyd died after being arrested by police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and his death echoed across the world.

A white police officer called Derek Chauvin was filmed kneeling on George Floyd’s neck and in the UK the Black Lives Matter movement told us his terrible death was our shame, too.

The Black Lives Matter movement stated its aim was to bring justice, freedom and healing to black people across the globe. Few Brits would disagree. But BLM is also a radical political movement which openly seeks to overthrow capitalism and, in this country, its violent protests made them toxic to many.

It felt like we were at war in 2020 as the virus changed, mutated and searched for new ways to inflict fatal harm. The good news was that the UK has the best analysis of these virus mutations — DNA genome sequencing — on the planet.

The bad news was Health Secretary Matt Hancock used the discovery of a more infectious Covid strain in December to terrify us into lockdown comp-liance and his words spread panic.

Voice of calm

More than 50 countries across the world, many of them with worse infection rates than the British, immediately shut their borders to the UK. Ironic, as the British-made Oxford-AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine was just days away from approval. But as Covid-stricken French President Emmanuel Macron cackled and coughed behind his face mask, thousands of lorries were gridlocked at Dover and the army had to be called in.

Yet the year ended in a moment of truly historic triumph for this Tory Government and Boris Johnson.

The PM’s critics were growing in number in 2020 but he confounded the lot of the them. Boris was elected with the promise to “get Brexit done” and when a trade deal with the EU was agreed at the last moment, he emphatically delivered.

The Queen had been a voice of calm, sanity and inspiration at the start of the year, and so she was again at the end. In her Christmas Day speech, she revealed a genius for capturing the mood of the nation she has served for so long.

“We need life to go on,” she said. resplendent in purple and pearls. “Even in the darkest nights, there is hope in the new dawn.”

But the wretched year of 2020 ends with a spectacular triumph for our country — the vaccine getting rolled out here before anywhere else in the world.

While the lethargic EU is still getting its lederhosen on, 137,897 Brits had their jab in the first week alone, all of them old enough to remember the Second World War.

They all grew up with sacrifice, they all understand how fragile life is, how quickly everything can change. Perhaps some of that generation’s appreciation for life’s real treasure will rub off.

“Have yourself a merry little Christmas,” said Boris, just before he unplugged the lights for a Christmas unlike any we have ever known in peacetime.

But then Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas was first sung by Judy Garland in 1944, a song for Christmas during wartime and enormously popular with servicemen far from home.

It seems an appropriate song for 2020, with its heart-breaking promise that can bring a tear to every eye:

Next year all our troubles will be miles away.