SCIENTISTS are working on a cancer vaccine which will be personalised for individual patients.

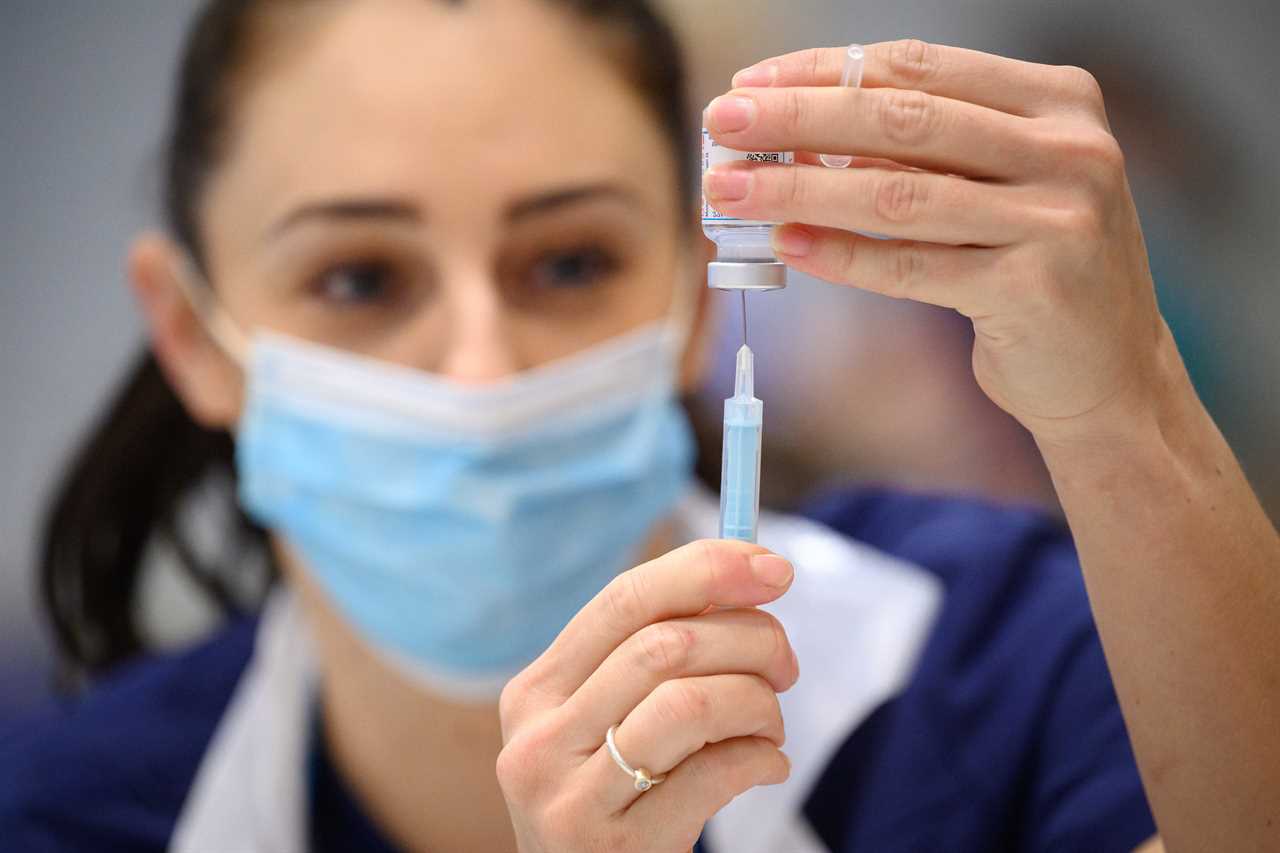

The new jab will be used to treat treat patients with high-risk melanoma – the deadliest form of skin cancer.

Melanoma takes the lives of 2,340 people per year

The game-changing vaccine, which could prevent thousands of deaths each year, is in the second of three trials.

Manufacturers Moderna and Merck have said results of the trial, which will determine whether it stops cancer coming back, are expected by the end of the year.

The experimental vaccine is based of of the same messenger RNA (mRNA) technology that was used to create the revolutionary Covid vaccines.

The cancer shot is tailored for each patient to generate T-cells – a key part of the body’s immune response – based on the specific mutational signature of each tumour.

mRNA vaccines are usually cheaper to produce than traditional vaccines.

However, personalised vaccines are very expensive.

There are various forms of skin cancer that generally fall under non-melanoma and melanoma.

Non-melanoma skin cancers, diagnosed a combined 147,000 times a year in the UK, kill around 720 people a year in the UK.

Melanoma, meanwhile, is diagnosed 16,000 times a year, but is the most serious type that has a tendency to spread around the body.

The deadly cancer takes the lives of 2,340 people per year.

How do mRNA vaccines work?

Conventional vaccines are produced using weakened forms of the virus, but mRNAs use only the virus’s genetic code.

An mRNA vaccine is injected into the body where it enters cells and tells them to create antigens.

These antigens are recognised by the immune system and prepare it to fight the virus.

No virus is needed to create an mRNA vaccine.

This means the rate at which the vaccine can be produced is accelerated.

As a result, mRNA vaccines have been hailed as potentially offering a rapid solution to new outbreaks of infectious diseases.

They can also be modified reasonably quickly if, for example, a virus develops mutations and begins to change.